Today’s subject: 650c vs. 700c wheels on smaller bikes

A quick word about wheel size: 650c is a smaller size than 700c. It’s a not a huge amount (We get into that in a few days) but it’s certainly visually noticeable when next to each other.

This is a series of eight articles that we’ve put together to explain the challenges that bicycle manufacturers face when building bicycles for petite cyclist with big wheels. It should put to rest several myths by educating you in the area of bicycle geometry as it relates to fit, safety, handling and practicality. These articles may seem basic to those in the industry, but are written for those not in the industry. Over the next several days, we will post, one at a time, the series. Thanks for reading, and I hope the information is helpful for any petite cyclists out there that are being bombarded with conflicting advice.

Now on to the overview and reasons for the series.

The quick overview of this series for those who don’t need massive amounts of info

Although they can be made to look normal, 700c wheels on a small bike always results in one or more unavoidable compromises.

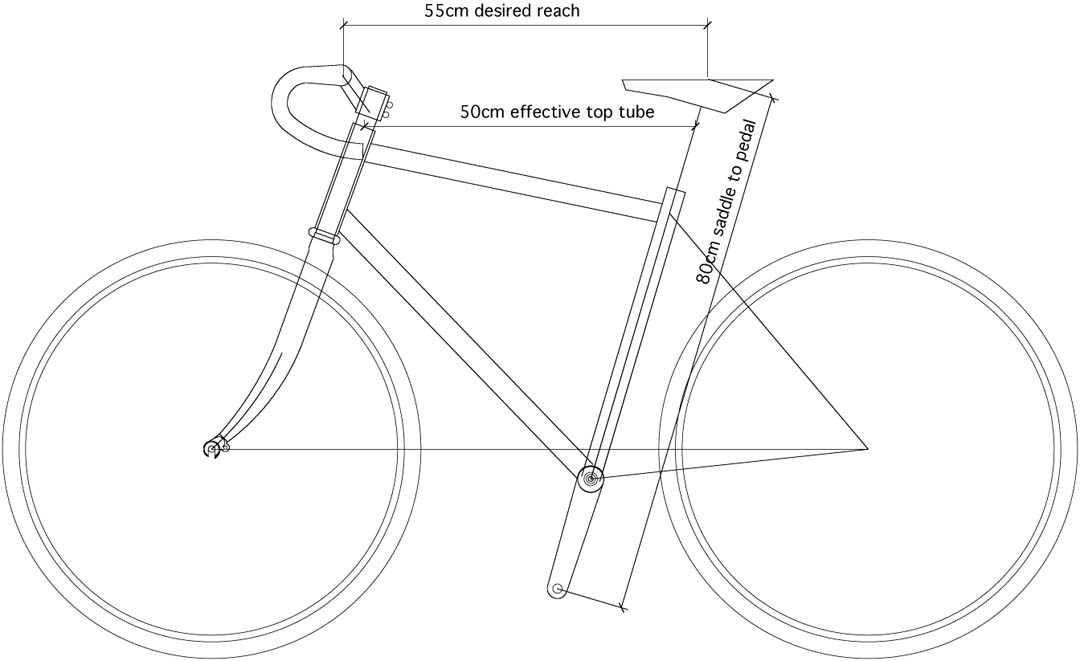

Although 650c wheels allow us to design a smaller bike to handle great and fit comfortably, they do result in a few compromises.

Obviously if there were no downside to 700c on every bike, then that’s all we would offer. But, there are several drawbacks, and that’s why we offer 650c wheels as an option for smaller bikes.

Now, maybe you want to really understand the subject before you commit? Maybe you’re the type that needs to arm yourself with some technical facts before you brave the conversation with ‘the bike expert’. For those of you who really want to have a grasp on the subject, I’ve written more….a lot more.

Who this series is for:

- Anyone who is under 5′ 5″ tall (especially women), has long legs, and is shopping for a bicycle.

- Anyone who is advising someone who is under 5′ 5″ tall about bicycles and what to look for when selecting the proper size.

- Anyone who likes to read nitty gritty details from the mind of a crazed bicycle frame designer who’s spent his entire adult life designing bicycles.

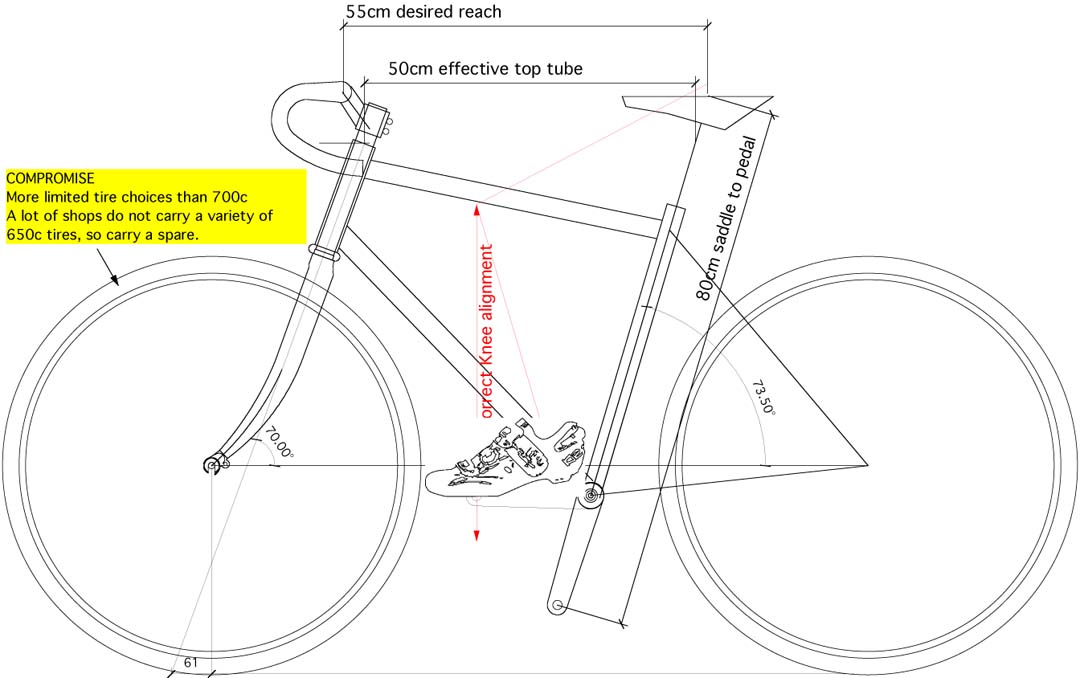

Terms you’ll want to understand for this series:

- Fork Rake – Offset that places the fork ends ahead of the steering axis

- Head Tube Angle – The angle that the frame holds the fork at in relation to the ground (same as steering angle)

- Trail – The distance that the axle trails the steering axis intersection with the ground

- Effective Top Tube Length – The measurement from the center of the seat post to the center of the head tube when measured level

- Reach to Bars – Distance from center of seat to center of handle bar stem

- Proper Knee Alignment – Adjustment to ensure that your knee is centered over the pedal spindle

- Seat Tube Angle – The angle of the seat tube in relation to the ground

- Toe Strike – How much of the foot interferes with turning the front wheel

Disclaimer: I’m not trying to sell anyone on a specific wheel size. Realize as you read this series, we are happy to build any size bike with any size wheel. I just want to show why we offer smaller wheels for those who need smaller bikes. We build small bikes with 700c wheels all the time as some people are willing to accept the performance compromises that are unavoidable.

Bike Industry Misinformation

There is a lot of misinformation that is spread throughout the cycling industry about bigger wheels and smaller wheels. There are reasons for this, but this article is about why we do what we do. If you want to delve further into the misinformation I go into that here. For those that have already heard it, and just want to get educated on the subject, read on.

Oh yeah, if someone at a bike shop tells you that 650c wheels are slow (it happens all the time), ask them if you can test ride one of their slow 650c wheel bikes to see for yourself. Chances are, they don’t have any, and probably have never even ridden one. Why would they have ridden a 650 bike if they are over 5’4″ tall? If you’ve been told this, and want to read more on the subject, that’s here.

Why Compromise? Well, sometimes you just have to.

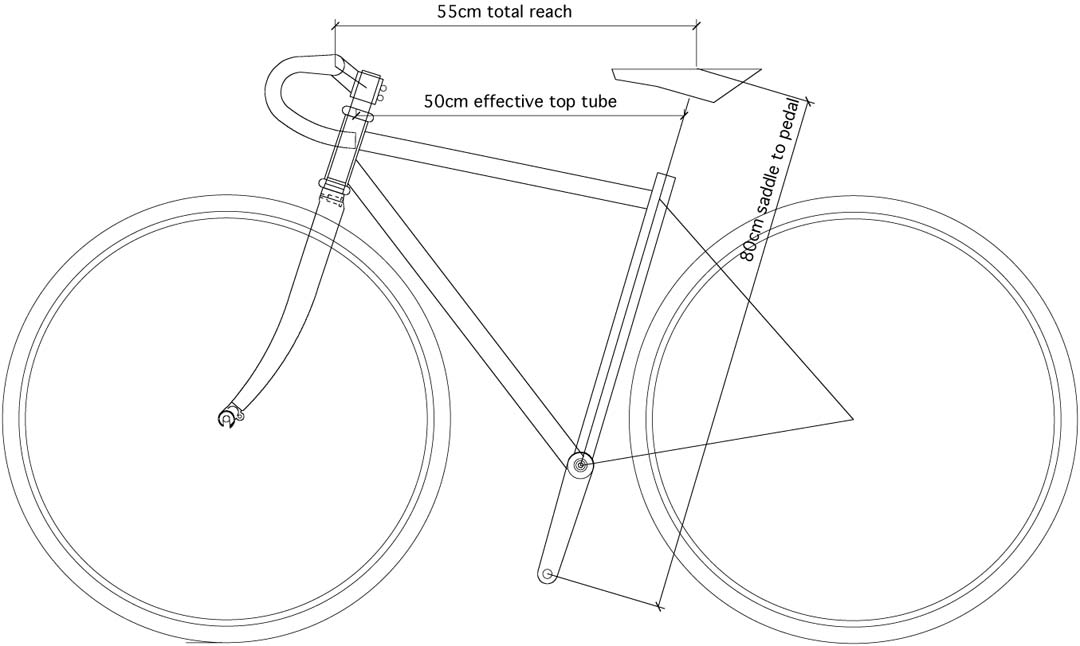

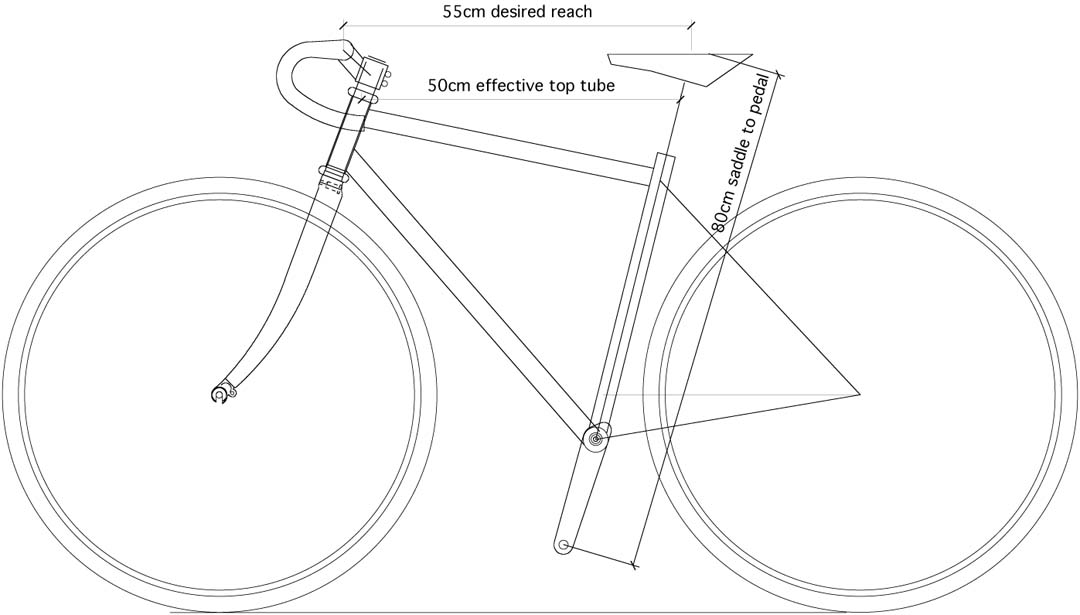

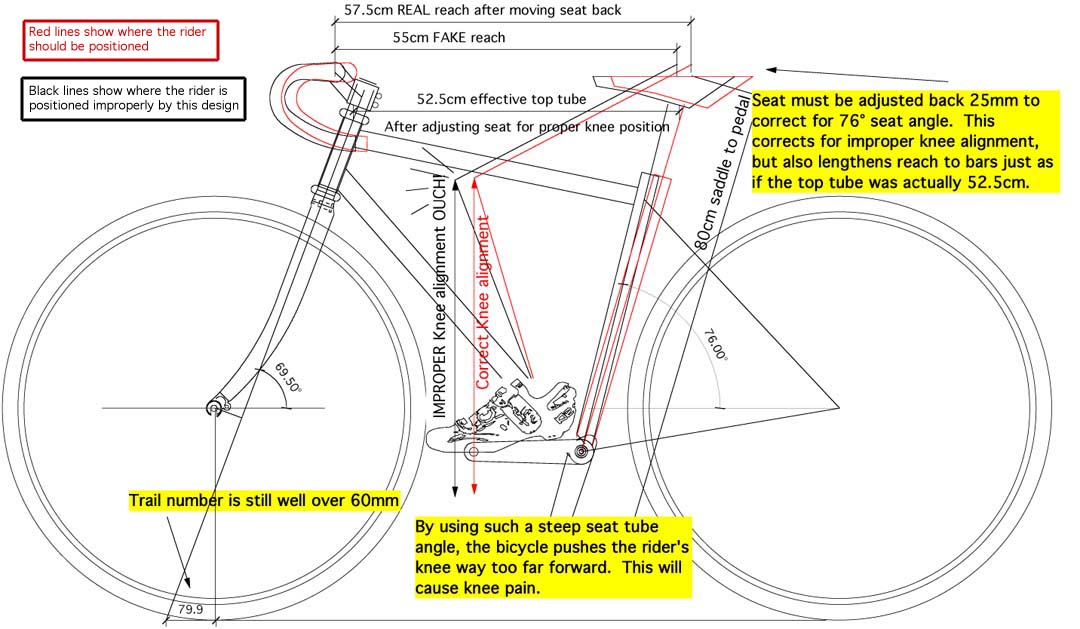

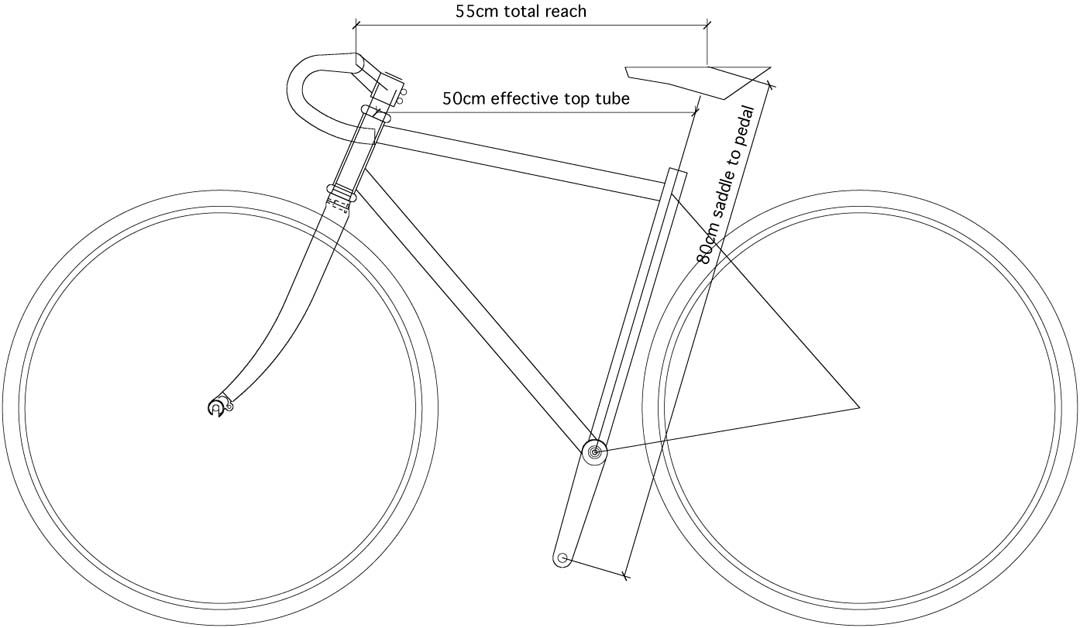

If you ride a modern bicycle with a top tube shorter than 54cm, and the wheel size is 700c, you’re already compromising. This series is to inform you of the compromises that are made throughout the bicycle industry when designing bicycles for riders under 5′ 5″. It is very technical, and ventures into eye glazing geometries. If you read it well, and understand it, you will be more educated in the subject of bicycle design than most folks who actually work in the bicycle industry. My goal is to help the more petite cyclists among us make an educated decision based on physics and truth. Along the way, I’ve linked to some information that will dispel the myths that have been regurgitated for years in bike shops and magazine articles.

Example of toe strike on smaller race bike

Example of same size bike with no to strike

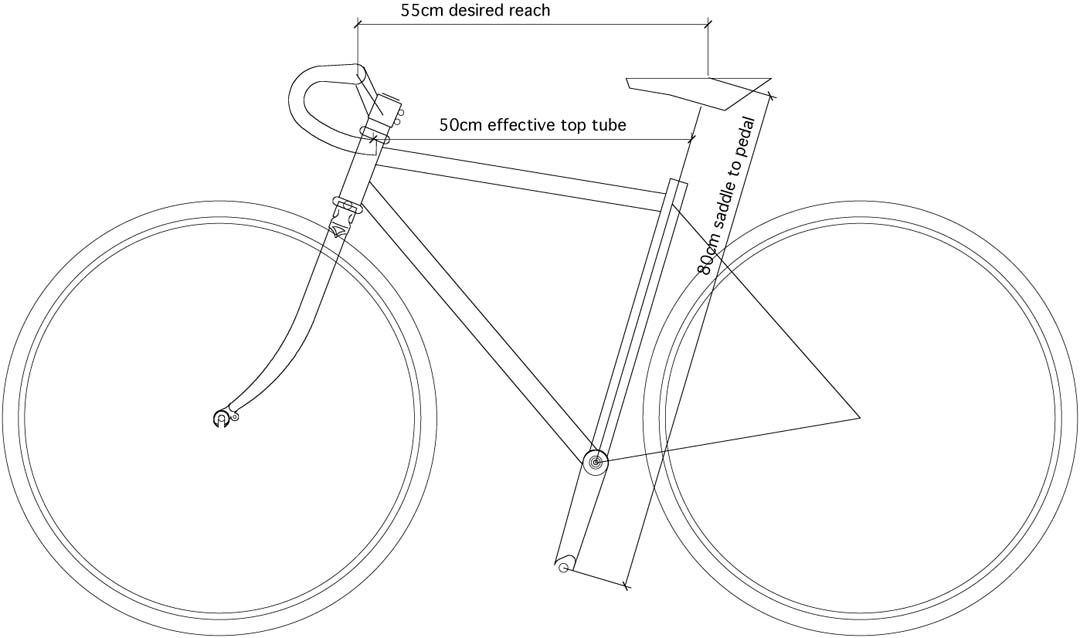

So, why do some bike manufactures suggest smaller wheels on smaller bikes?

Short answer: Because they want to offer the petite rider the same performance and comfort as they do the taller rider. It all boils down to something called Toe Overlap or Toe Strike:

If your front wheel overlaps and hits your foot when you turn, this is called ‘toe strike’. The smaller a frame becomes, the closer the front wheel gets to the rider’s foot. A small amount (maybe 1/4″ or so) of ‘toe strike’ can be common on modern race bikes, but more than 1/4″ can be quite a nuisance, or even dangerous, especially if the rider wants to use fenders.

Good Design

A smaller wheel allows us to produce a shorter reach frame with the proper head tube angle for good control while at the same time minimizing any, if not all, toe strike. Using a 700c wheel on a bike with an effective top tube of less than 53cm requires design gymnastics (or in some cases, cheating a little) to keep this from happening. Design gymnastics result in improperly fitted bikes, or bikes that handle poorly.

In the 1980’s smaller high performance bikes had 700c wheels. What happened to those good designs?

The Carbon Age – Now that carbon forks are the norm on just about all competition bikes, they must be purchased from manufacturers who do not offer products with rakes required to accommodate really slack head tube angles. If we could custom make carbon forks one at a time, the way we used to make steel forks, then we could pull this off, and our jobs would be easier.

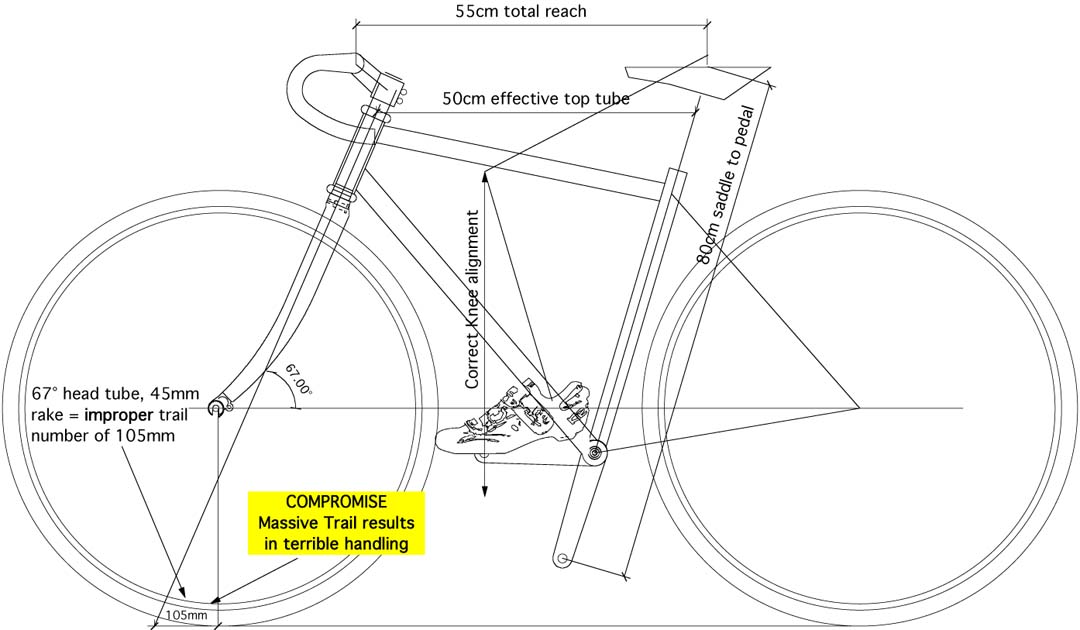

Trail Mix

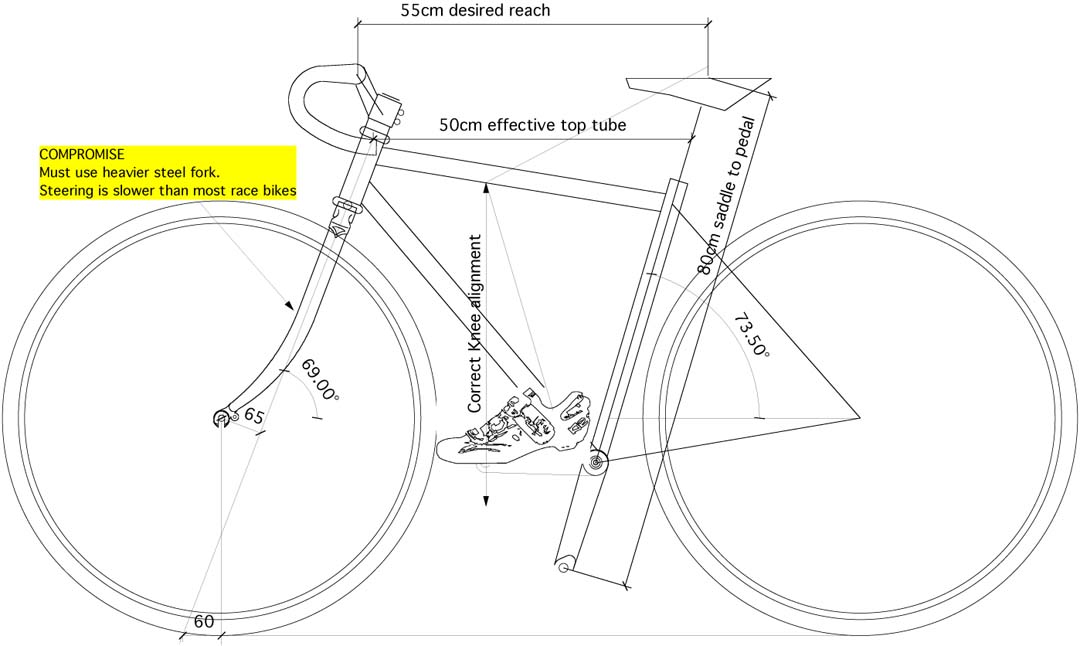

Something that most people don’t realize (including many who work in bike shops), is that there are good reasons for the head tube (steering) angle and fork rake as they relate to the handling characteristics of your bicycle. They are entwined with each other, and when one changes, so must the other. The trail number is dependent upon the combination of the two, and ignoring it will result in a bicycle that doesn’t handle properly. The desired trail number for most purposes is 60mm or somewhere very close to it.

If you want to have some real fun, ask your bicycle salesperson “what’s the trail on this bike?”. It’s a good way to determine the experience level of your salesperson.

Why did steel work better?

Steel forks offer much more flexibility for bicycle design. Years ago (1990 and before), we built lots of small bikes with 700c wheels and steel forks. We could change the head tube angle to a more ‘slack’ degree to move the wheel further out in front of the rider and then build the fork with more ‘rake’ to accommodate proper handling. The more ‘slack’ the head tube angle, the more ‘rake’ is required in the fork to maintain the appropriate ‘trail’ number of 60mm. The added rake moved the wheel out even further.

The very best way to put a 700c wheel on a smaller bike in 2012 is the same way that we used to do it in the 1970’s and 1980’s…..use a steel fork. By using a steel fork, we can keep the handling characteristics acceptable, and still build to the proper fit and knee angle.

The things I’ve seen:

Smaller bikes with 700c wheels and modern carbon forks have been made by many manufacturers, and I’ve probably seen them all in the repair shop. The compromises used are many. Here’s a list of the compromised designs I’ve seen:

Really bad option: No compromise, completely ignore proportions

Some manufacturers don’t even pretend. They simply make the small frames with a 54cm top tube, just like their bigger frames. So the reach to the handlebars for a 5′ tall rider is the same as the 5’8″ rider. Many women have ridden this way most of their lives, and they think bicycles just have to be uncomfortable.

I actually appreciate this approach simply because it doesn’t pretend to be something it’s not. This will provide the proper stand-over height, but a shorter rider’s reach to the bars will be a long trip and a very uncomfortable ride (sore neck, back, arms, shoulders, etc.). Many shorter riders know what I’m talking about as they’ve never been offered a proper fitting bicycle for most of their life.

Now, if you’re of smaller stature or need a top tube length less than 54cm, and you want your bike to fit right, there’s a number of compromises that you can choose from. Some of these compromises are much better than the others, and some are meant to fool you.

Tomorrow’s article:

Wipe-out! Some manufacturers are building dangerous bikes for their petite cyclists.

Click here to continue your study.

Related Items