Being a small builder has it’s challenges. Our goal has always been building a bike that fits well and meets all the customer’s performance needs. Sounds simple enough, but a lot goes into it. We couldn’t do it without a manufacturing system that’s both efficient and versatile. It’s the core reason why we can offer a bike built just for each customer that’s exactly what they’re looking for. Today I’m talking about some of the steps we’ve taken to make that goal possible in today’s bicycle world.

In 2005, we radically redesigned our manufacturing process. We went from a traditional batch method of bike building to a true “one at a time” custom building process. We did it in such a way that both saved time and made our system almost infinitely flexible. How is that working out almost 15 years later? Turns out it’s more relevant than ever.

The traditional method for building bikes involved making batches of frames that were all the same. This is still done on a large scale by the major (and some less major) manufacturers. A set of sizes are designed and a number of each size is made depending on how many the maker thinks they can sell. This is great if you ride a medium size and your body is of medium proportions. There’s always a bike for you in the world. This is less great if you need a size that’s unusual or a size that’s in between the common sizes. It’s also a problem if you want special features not included on the production model, or specific performance characteristics from the frame. That’s where builders like R+E come in handy.

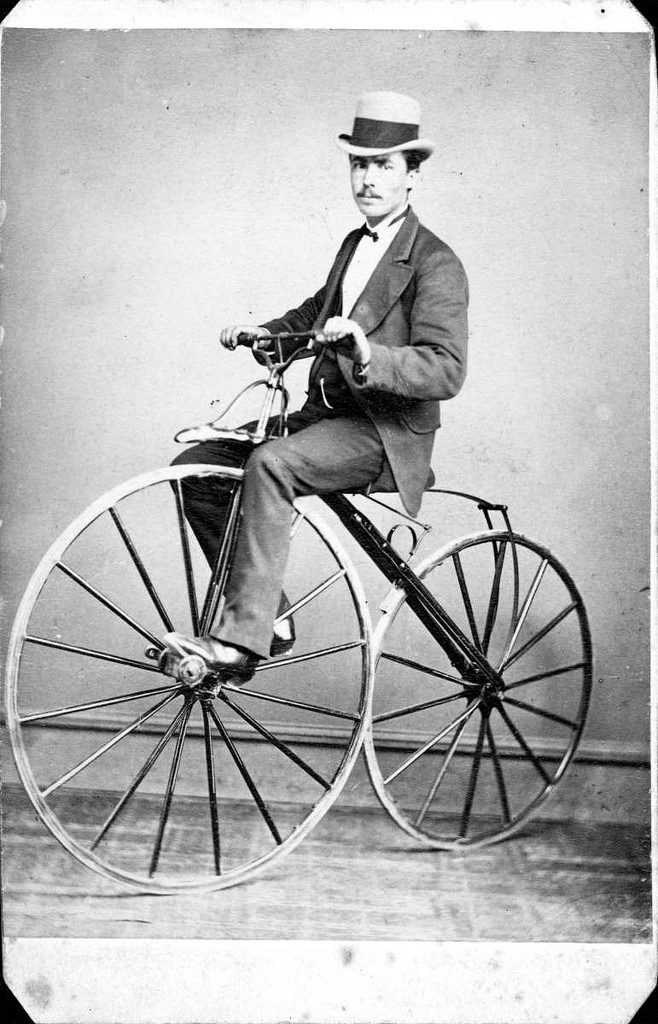

In the beginning (the mid 70’s) we would also build batches of bikes in order to save time in the frame shop. Bikes were built using lugs, which limited the frame design somewhat so there wasn’t as much variance between frames like you see in modern bikes. A road bike was a road bike. A touring bike was also pretty much a road bike, just slightly different. Mountain bikes hadn’t happened yet. Batches made a lot of sense under these conditions. This didn’t change much until the late 1980’s.

The 80’s brought us a plethora of new technologies that reshaped bike design. Tig welding freed us from the strict design needs of lugs. New tubing choices in steel, titanium, and very early carbon fiber (then called graphite) became more available. The radical design needs of mountain bikes started to redefine what a bike could (or should) look like. Bikes started to become much more differentiated as we moved into the 90’s. Road bikes, touring bikes, and mountain bikes started to look very different from one another.

As a custom builder, we also started varying our designs. Rodriguez developed the Stellar, one of the first bikes designed specifically for women. It wasn’t just a bike with a lowered top tube, but one that took into account women’s smaller stature and fit needs. Tig welding and new mitering tools allowed us to build bikes with new geometries that didn’t have to make as many compromises for smaller riders. However, we still did a limited number of production sizes and built bikes in batches whenever possible. Our milling machine had to be set up from fresh for each new process so doing multiples made sense

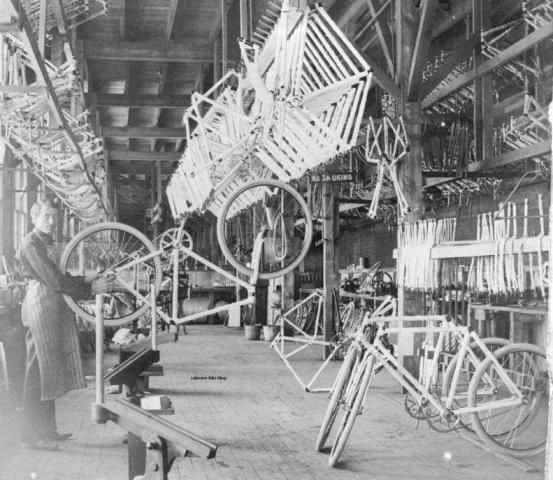

By the early 2000’s the bikes we were building had become more individually specialized than ever before. Each model had a very different set of requirements and we had expanded our sizing range to better accommodate our customers. Batching became more difficult and less valuable. Our framebuilders were losing time waiting for machines to be freed up and bikes were taking longer to finish. We knew we had to change our process.

Starting in 2004, we made several significant changes to our production model. Instead of a couple of versatile machines doing everything, we switched to several smaller machines that did just one thing really well. Once set up, these machines virtually eliminated idle time due to machine setups and changeovers. Our framebuilders could finish a frame much more quickly without sacrificing quality. Our new tube mitering machine could miter tubes of different diameters and cut different angles much more easily as well. Our builders were suddenly able to build a standard frame from scratch in less than a day. This freed them up to build much more elaborate and complicated designs without the entire production process coming to a halt.

In 2019 we can see that all of these changes weren’t just beneficial, but vital to the direction bike design has taken. There are more differentiated styles of bike now than ever before, each with their own idiosyncrasies. Gravel bikes, road bikes, touring bikes, city bikes, randonneuring bikes, and mountain bikes all have different manufacturing requirements. If we need new tooling or equipment for a new feature or component, we build or buy what we need and it gets incorporated into our tool set. Being a small builder requires a high level of manufacturing versatility and we’re lucky to have started working that way as soon as we did. It’s allowed us to evolve to meet the needs of customers more easily without having to resort to lengthy wait times or compromises in quality. That’s exactly the kind of builder we want to be.

This post is an update to an article Dan wrote in 2006 about or then new process.

This article details our journey towards the perfect bike fit.

This one talks about bicycle sizing and how yours is determined.