Material World

(this article was run in four parts in The Bicycle Paper through the summer of 2009)

Ever since I can remember, bicycle makers have tried to find the ‘perfect’ material to build a bicycle frame that was the lightest, safest, most comfortable, durable, responsive frame ever made. In short, they’re looking for the ‘Miracle Material’. In today’s high-end bicycle frame market, customers will often decide on a brand of bicycle based on the material the frame is made from. There’s steel, titanium, carbon fiber and aluminum. There’s certainly others like bamboo, magnesium, etc., but we’ll try to limit this article to the four most commonly used in today’s bicycle frames. Which one is best? What are the differences?

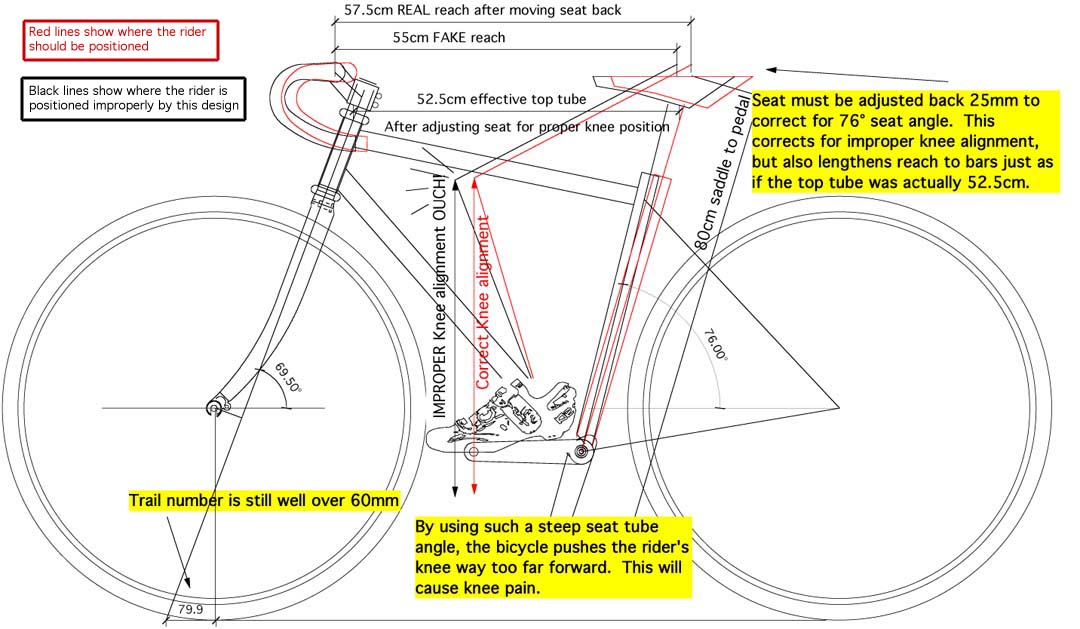

If you know me, then you know that first and foremost I think that a good fitting bicycle is the most important factor, and things like components or frame material are always second to that. That being said, there is a lot of information and opinions that a bicycle shopper is exposed to when discussing a new frame. Keep in mind that I’m no engineer, and I’m not going to pretend to be one. We have been designing, making, selling and repairing bicycles full time here in Seattle for several decades now. I have been riding, building, selling, fixing, destroying, customizing and loving bicycles since I was given my first one at the age of 6. It is from these experiences that I draw on to write an article like this one.

You’ll notice that when I refer to weights, I refer to things I’ve actually weighed. This is because I find that most manufacturers either have poorly calibrated scales or they…..well….stretch the truth a bit. It’s kind of like my Uncle Earl and his ‘Fish that got away’.

I’ve been trying to decide the best way to analyze this topic without delving so deep that the entire issue will be consumed by my ramblings, and I think I’ve come up with some relevant filters.

I don’t think I have the time here to compare every price range, so we’ll limit this article to higher end and custom frames….let’s say frames that cost over $1,000. We can also filter out the mass-produced frames from Asia (that could be a book long analysis in and of itself).

We’ll compare cost, durability (longevity), versatility, repairability, and the all important ‘ride quality’, of the four common materials. I’ll also throw in a little ‘wrap-up’ section at the end.

Aluminum:

Very quick history:

Aluminum has been used in bicycle manufacturing since the 1890’s. A quick Google search for aluminum bicycles of the 1900’s will turn up very modern looking bicycles from the 1930’s made with aluminum frames and aluminum forks. Aluminum has the advantage of ‘no paint needed’ if you like that aircraft industrial look.

Peugeot aluminum bicycle circa mid 1900’s

Photo – blackbirdsf.org

When I was kid, all bikes were steel. Not just any steel though, they were really, really heavy steel. It wasn’t until the mid 1970’s that Vitus and Alan introduced aluminum frames that I lusted after. These frames resembled conventional frames but had anodized finishes instead of paint and were very light weight (in comparison to the steel frames of that day). The ride was very soft, and worked best for riders who were of lighter weight, and rode with very high cadences.

About that same time, Gary Klein came out with a new aluminum frame that used super fat tubes and a neon painted finishes. It looked completely different than any frame I’d ever seen before. In the 1980’s, Cannondale followed suit, and the oversized aluminum craze took off!

Eventually, these oversized aluminum beasts gained a reputation of being so stiff that they were uncomfortable to ride. This was my experience when I commuted almost 40 miles 3 days per week on one of these frames for nearly 2 years. Soon, riders were running for the Ibuprofen, and scheduling appointments with their bike fitters.

Modern day aluminum:

While in the 1980’s customers thought of aluminum as expensive and lightweight, today, the story is very different. Just as any great thing eventually turns into a fad, heavy, huge, fat aluminum frames have pretty much taken over the lower end bicycle market. Just because it’s made of aluminum does not make it light. One visit to Toys-R-Us to lift the 40 pound aluminum monsters will prove that. There are still however some light weight, high-end, custom aluminum offerings. We also build a lot of the super long bikes (triples, quads, and quints) from aluminum.

Expect a high-end, light weight aluminum frame to be 3 pounds or a little more. On occasion I’ve weighed one in under 2.5 pounds, but those are usually very small sizes and very expensive custom frames.

Cost:

Custom light-weight aluminum frames can be built for a fairly reasonable price. Expect to pay $2,000 to $3,000 for a custom aluminum frame with fork built to your specifications.

For a custom builder, it takes more time to weld an aluminum frame, and the aluminum ends up costing a bit more to mitre and shape as it clogs the equipment faster than steel. It also has to be heat treated after welding, adding to the time and cost. These extra costs show up in the retail price of custom aluminum frames, but the actual material is relatively inexpensive.

Durability (longevity):

Warranties vary on aluminum frames. Some companies offer lifetime warranties, and some offer just one year warranties. I feel that most aluminum frames are very durable, and will last a very long time. Although, over-sized aluminum does have a very non-forgiving characteristic – if it is over-stressed or cracked, it can fail very abruptly. Because of this characteristic, it is important to inspect aluminum frames after an accident for any sign of cracking or stress, even if the bike rides perfectly. Some manufacturers put a warning sticker right on the frame advising the owner to inspect frequently for cracks.

The super light aluminum bikes will not last forever, and aren’t advertised that way. On the other hand, I see a lot of the old original Cannondale and Klein frames still on the road after all these years. As a matter of fact I saw one of those original 1983 ~ 1984 Cannondale bikes in the repair shop for a tune-up just yesterday. I also have a neighbor that rides his Vitus aluminum frame as his daily commuter, so I’d have to say that aluminum as a material can have a very long life span if not damaged.

Versatility:

When building a custom frame, aluminum is a versatile material. It’s available in many weights for different riding styles and rider weights. When building extremely long bikes like a triple or a quad, aluminum offers a light-weight, reasonably priced alternative to steel. After the frame is built and heat treated though, that’s where the versatility ends.

Aluminum machines easily, and is readily available in our area so it’s easy enough for us to machine any frame fitting or dropout that’s not available to order.

Repairability:

Repainting an aluminum bike is always possible. It’s more labor intensive than steel because paint has to be chemically stripped off of aluminum. Since we don’t offer chemical stripping services, our aluminum bike customers….well they’ll have to do the stripping themselves.

As far as frame repairing goes, aluminum is not very repairable. After it’s welded, an aluminum frame must be heat treated. Once it’s been heat treated, further structural welding will weaken the frame. Sometimes very small things can be fixed, but if something crucial breaks or bends, the frame is done for.

If you wind up in a pinch somewhere, you’re probably not going to get your aluminum frame repaired.

Ride Characteristics:

For the most part, oversized aluminum frames are very stiff and unforgiving. You’ll get good transfer of power through the cranks to the wheel, but suffice to say that the ‘thud’ sound you hear if you flick the frame with your finger nail, is the same ‘thud’ sound you’ll feel when riding on pavement or bumps. You’ll feel the road transferred to your ‘contact points’ through a very unforgiving frame.

Tight corners on bumpy roads will require more slowing down for control purposes as the bike can ‘bounce’ or ‘rattle’ out of the groove if your not careful.

Not to characterize all modern aluminum bikes the same though, Scandium aluminum from Easton claims to ride more like a steel frame. I’ve ridden a Scandium frame that was my size, and it rode much nicer than my other oversized aluminum frame, but I wouldn’t say it had the liveliness of steel.

Carbon Fiber:

My brief (and rather limited) history with carbon bicycle frames:

First, a bit of mythbusting:

Most people think of carbon frames as fairly new to the industry as well as being ‘uber light-weight’. Fact is, there are some very light carbon frames out there, but no lighter than the ‘uber light-weight’ offerings in aluminum, titanium or even steel. If weight is important to you, then it’s important to actually weigh a frame yourself on a digital scale before you buy it.

I’ve been turning my office upside down this morning looking for one my old Bicycling magazines that had a picture of an old Rodriguez graphite (carbon) frame. Low and behold, in an old dusty filing cabinet behind a wooden dresser in the warehouse, I finally found it. I had to page through many of my old magazines to find it, but that was fun too.

Here it is straight from Bicycling Magazine, November of 1975, a Rodriguez Carbon track frame. For those of you who wonder if we’ve ever built carbon bikes here in Seattle, the answer is yes. Note: (Even the 1975 photos were provided by The Bicycle Paper.)

Angel Rodiguez hand-built Carbon Frame – 1975

Photo From Nov. 1975 Bicycling Magazine

Dennis, our head frame builder (through 2012), also built a pair of carbon fiber tandems for a world record setting ride back in 1987.

Now, I’m not quite as old as those guys (I was 10 when Angel built that frame), so my history with carbon fiber goes back to the early 1980’s when I worked a summer at a Peugeot/Schwinn dealer. They had an extremely expensive Peugeot that was made from carbon fiber, but I wasn’t allowed to ride it. I never saw anyone ride it actually, but it sure looked cool on the top rack in the shop. Every time I see one of those Peugeots I kind of want it, more because of it’s looks than anything else.

In the late 1980’s I started work here at R+E Cycles. We sold Kestrel carbon frames that were roughly 3 times the price of a nice steel frame at the time. The design was much more like the modern molded and shaped carbon bikes. By comparison, these frames were much lighter than steel (at that time), as well as the aluminum Cannondale and Klein frames that we sold.

During this time, I ran the repair department, and we assembled all of the upper-end bikes. I got to ride Kestrel frames on several occasions, but really never rode one more than 5 minutes at a time. The ride of these frames was not attractive to me, and I could only describe them as ‘dead’. I would say that the ride was as dead as an oversized aluminum frame, but for the rider looking for the lightest frame they could get, this was the best option if they could afford it.

Modern day carbon frames:

Like aluminum, carbon went from being the ‘untouchable’ super light frame on the top rack to a more affordable version. The ‘uber light’ versions are still very expensive, but Taiwan and China are now cranking out heavier, less expensive carbon frames in record numbers. I have never ridden a carbon frame that made me want to buy one, so my experience is limited to that of my customers who do have them.

Carbon as a material is pretty versatile because it can be molded into just about any shape that you want it to be. Then those shapes can be used to add strength where needed. It has a very strong strength to weight ratio, and is replacing aluminum in a lot of aircraft manufacturing.

I’ve seen carbon frames advertised at 2 pounds, but on my digital scale those same frames weighed 2.5 pounds. When we checked into the discrepancy, we found that the advertised weights did not include the bottom bracket shell or the dropouts. Most people want to have their cranks and wheels attach to their bicycle, so we always quote weights that include the bottom bracket shell and the dropouts. 😉

Cost:

Custom carbon fiber frames are pretty expensive. Mass produced production models have become affordable over the last few years, but in the world of custom bikes, expect to pay about $2,500 to $5,000 for a custom carbon fiber frame with fork built to your specifications.

Durability (longevity):

This was an interesting quote that I came across while researching for this article.

“DO CARBON FRAMES LAST?

Yes. [Our] frames are guaranteed for five years of racing and training use. When the primary consideration is performance, carbon is the only choice. If you really need your frame to last for fifty years, buy a steel one.”

Believe it or not, it is a quote from a major carbon frame manufacturer from the FAQ section of their website. I think it is worth pointing out that the frame in question here is a $4,000 frame, and the manufacturer thinks that 5 years is a reasonable life for such an expense. Let’s see….$4,000 over 5 years (60 months) = $67 per month. The warranty excludes damages from “extremes of temperature, or the effects of UV light”. Isn’t that sunlight? OK, we don’t have to worry about that one here in Seattle 😉

I also strongly disagree with the statement ‘carbon is the only choice for performance’. This is obviously a very un-researched opinion. Maybe they need to read this article;-)

What my personal experience says about the durability of carbon frames is that when they fail during an impact, it usually looks catastrophic. On one occasion a customer brought her broken frame in for me to see. The frame actually had broken in half after she hit a curb. The 2 halves were separated completely, and the customer broke her collar bone so she was in pretty rough shape. The frame was probably 10 years old, and she did hit a curb going fast, so a frame failure is not surprising. However, this failure was much more dramatic than I’ve seen on aluminum, titanium or steel frames under any rider accident circumstance.

She replaced that carbon frame with a steel frame.

Side note:

I have heard of an occasional aluminum frame breaking in this same catastrophic fashion, but due to defective welding, and not due to age, accidents, or damage from the sun. In those cases, the frames were virtually new, and failed under normal use…not that that’s any comfort ;-(

As far as longevity of carbon frames, I don’t see a lot of old carbon frames out there. Certainly the ones from the 1970’s and 1980’s are very, very rare to see. The occasional old Kestrel rolls in for some work in our repair shop, but for the most part I can’t say how long a carbon frame will last if ridden all the time. I can tell you that the company quoted above thinks that 5 years is a long time for a carbon frame to last. I know that some manufacturers do warranty their carbon frames for 25 years, and some for life, but if you look real close you’ll find that there is still some planned obsolescence in a few of those warranties. To explain that understandably, I’d have to delve into proprietary parts manufacturing and that’s a whole article in and of itself.

I think all in all I want to see a number of old carbon steeds that have been used as commuter bikes for maybe 20 years or so before I can recommend carbon as a very durable custom frame material.

Versatility:

Modern carbon frames that are mass produced are built with a mold. This isn’t a cost effective way to build a custom frame as the molds cost a lot money to make. So, for a frame built especially to your dimensions, the frame is built in a different fashion. Custom carbon frames are built kind of like the one pictured in this article from 1975. The tubes are cut and mitered, and then attached together. Some are glued into lugs, but most modern frames are wrapped with carbon fiber fabric and then coated with an adhesive resin.

I think that the versatility of carbon fiber has a lot of promise. As far as custom frame building goes, there’s not a lot of small bicycle frame shops that are insured and set up to build or repair carbon frames. In modern times, we’ve used a few carbon rear triangles upon request., but these are pre-fabricated. Apart from that, we haven’t found the need to switch to the material as customers don’t come to us often for carbon.

Repairability:

Every year I have customers who would like to have me paint their carbon frame. Some carbon manufacturers will void their warranties if the frame is re-painted because most methods of removing the old paint will cause structural harm. Sometimes we’ve painted carbon frames but more times than not, we can’t do it. We won’t remove old paint from carbon frames with chemicals or heat, so paint removal can be very costly. In short, if you’re a person who likes to have their bike painted different colors once in a while, don’t buy a carbon frame.

As far as fixing a broken carbon frame, like I said before when I’ve seen a carbon frame fail it was always something that looked unrepairable. I have a friend whose dog chewed through his carbon frame and he did have it repaired successfully. But, the repair was in a non-crucial area of the frame, and the work is kind of bulky and obviously a repair.

Again, there’s not a lot of frame shops insured and set up to fix carbon fiber bicycle frames, as most of the carbon frame manufacturers are overseas. So, at this point anyway, I would agree with the carbon frame company that I quoted above and say that carbon frames aren’t really meant to last forever.

If you wind up breaking your carbon frame, you’re probably going to need a new one.

Riding characteristics:

Carbon frames have evolved a lot since the 1970’s (so have aluminum , steel and titanium frames for that matter). There are carbon frames designed to ride smoothly, and there are carbon frames designed to be lightweight. Since I haven’t ridden one that made me excited enough to buy one, I will have to speak from my customer’s experiences on this topic. I would say that for the most part, modern carbon frames are reported to ride more comfortably than oversize tube aluminum bikes. Most of my customers prefer the ride of steel or titanium frames to the carbon frames, but I do have a few customers who prefer carbon.

Our head frame builder, Dennis, originally built his steel S3 frame with a carbon rear triangle, but after a year, replaced the rear triangle with an S3 steel rear end. The steel rear triangle was lighter than the carbon one, and he reported an increase in both hill climbing power and responsiveness.

Titanium (ti)

If you would’ve asked me 10 years ago to make a bet on the preferred frame material of 2009, I would’ve said it would be titanium. Titanium has been used for high-end bicycles since the 1970’s (and probably earlier if one did some looking). It only took me about 5 minutes to come up with this advertisement from August 1975 for a ti frame that was going to ‘change the world of cycling forever’. Titanium rides great, doesn’t need paint, plus the sun won’t damage it.

Early titanium frames proved to be a disappointment for me as the metal is so strong that the frames can be built too light. Too light, you ask? Yes, too light. Ti is very strong, but also very springy. I remember getting some titanium tubes for $1 each at Boeing surplus and setting one across a pair of milk crates. I could jump up and down on the thin-walled, super light tube to bend it several inches, but it would spring back every time. No matter how hard I jumped, the tube wouldn’t bend to it’s ‘crumple’ point (technical bike shop terminology). Well, when a bicycle frame is built from titanium to it’s ultimate ‘light-weightness’ (more bike shop technical terminology) so to speak, it acts like this thin-walled tube. This results in a frame that’s very light, but rides like a wet noodle. My first experience on a ti bike was an ‘uber light’ frame in the 1980’s. This colored my judgement until I rode a heavier Merlin ti frame in the late 1990’s.

Note:

Titanium didn’t take off like I thought it would as steel evolved so much that we can now build steel frames that ride great and are lighter than 3 pounds. That darn evolution, I didn’t take that into account.

Modern titanium frames:

We offered ti frames in the late 1980’s for a short time. We only recently started offering them again (back by popular demand).

You can still find some ‘uber light’ ti frames advertised out there, and even see a few of them on the road. Most ti frames however, are built around 3 pounds or so and ride very much like a high-end steel frame. Although it’s completely possible to build a ti frame well below that, if you’re my weight, height and riding style you’ll prefer a ti frame that’s 3 ~ 3.25 pounds….or 2.5 pounds if weighed by Uncle Earl 😉

Cost:

Well, I would say that titanium is on par with carbon fiber as far as custom frame pricing goes. Expect to pay $2,500 to $4,000 for a custom made titanium frame and fork built to your specifications.

Ti is difficult to machine, and requires a lot of extra steps to be taken during welding. The material is not as readily available as steel or aluminum, and is much more expensive to purchase. When you purchase a ti frame, you’re paying for twice the labor as a steel frame. The materials run about three times that of a high-end steel frame.

Durability:

A little more mythbusting:

In the bike industry, most people think of titanium as indestructible. While I believe that titanium is the most durable of all modern bicycle frame materials, it’s not completely indestructible like many people think it is. This winter alone, we’ve fixed three cracked titanium road bike frame of various makes. Some of the cracks were due to extreme circumstances, but some were just from regular wear and tear. As far as misalignment goes though, the material has such a memory that it’s very difficult to bend it out of shape permanently.

I would expect a ti frame to last forever. They’ve been around since at least the 1970’s, and I have no horror stories to report. When they break, they break like a steel fame. A tube might break at the welding point, but I have never seen a ti frame break in half and result in a catastrophic failure.

Versatility:

Ti is a versatile material to work with, but it’s limited availability and difficulty to machine, result in compromised aesthetics in my opinion. If my prediction would’ve come true, there would be hundreds of different dropouts and tubing manufacturers vying for our custom business, but that just wasn’t meant to be. Even so, I would consider titanium a versatile material that is great for just about any type of bicycle as long as the rider doesn’t mind paying a higher price.

Repairability:

There’s probably more frame shops in the U.S. insured and set-up to repair titanium frames than there are carbon shops, but the number is still very limited. We have been able to fix the ti frames that come to us for repair, but the ease of the job is somewhat limited to the materials available. For instance, if we need a certain diameter of ti tube to maintain the look of the bike, and that diameter is not available, then we have to improvise. This can result in a different look, maybe even a “wow has that been repaired?” look, but none the less it’s fixed.

As long as you are in a fairly large modern city, you can probably get your ti frame repaired if needed. Otherwise, your trip is going to be cut short.

Riding characteristics:

If the frame is built heavy enough for the rider, then the riding characteristics are fantastic. Ti frames ride smooth and responsive and stable. If the frame is too light (which is possible on a ti frame) then the ride is like a wet noodle. We have lots of customers who ride ti and love it.

Titanium and steel are my personal favorites for ride characteristics.

Steel

Steel has been used for making bicycle frames forever. No need to really go into the history here, as I’m sure just about everyone reading this has had a steel frame at least once in their past. Many people associate steel bicycle frames with ‘heavy’ because of the 50 pound Schwinn Varsity that they rode in high school. While it’s true that a steel bike can be very heavy, I’ve also shown that an aluminum bicycle can be very heavy as well. What it boils down to is cost. A cheap bike is heavy no matter what it’s made of. Steel bicycle frames can be as light as a $4,000 carbon fiber frame, and lighter than a $4,000 ti frame. Steel technology has evolved just like carbon, aluminum and ti has.

When I bought my first racing bike, it was a Peugeot steel frame equipped with all French components. It was light, but the frame was probably 5 pounds. I rode high-end steel bikes until I went the Cannondale route for a few years. I loved the ride of my steel Reynolds 531 Peugeot and I still have the frame hanging in the shop if you want to drop by and see it. I got it back from my step father whom I’d sold it to, and I’m waiting to have Teresa do a full paint restoration.

Steel bike frames in the 1970’s were advertised in bicycle magazines to weigh as little as 3.75 pounds, though I think Uncle Earl may have been writing their ads.

By the late 1980’s steel bikes seemed pretty heavy in contrast to the carbon fiber and aluminum frames.

Steel evolved through the 1990’s at a very rapid pace though. Since most custom builders are equipped to build with it, the steel tubing companies had an instant market for their products and didn’t have to ‘sell’ a builder on converting their entire operation to new material. Fittings and tooling for working steel are easy to get and relatively inexpensive, and it’s much easier to work with than the other materials.

In June 2009,

Road Bike Action Magazine an image of the steel Rodriguez Outlaw for an article about ultimate frame materials.

Modern day steel frames:

True Temper developed some new super strength tubing that was designed for the TIG Welding process. Eliminating the need for lugs lightened the frames as well as sped up the build process. It also allowed for more flexibility in custom design, and R&D projects.

When steel frames got down to lower weights than the aluminum frames, they started catching back on. The ride quality was seen as far superior to aluminum or carbon, so customers were willing to but up with a small weight difference if it meant a better ride.

Starting in 2009, we were building steel frames at well under 3 pounds. That weight includes the bottom bracket shell and dropouts 😉

So, instead of ti being my favorite all around bicycle frame material, steel remains my personal favorite.

Cost:

Steel is the most economical material for custom frame manufacturing. A custom steel frame with fork will set you back $1,200 to $3,000 built to your specifications. You can spend more on some of the froo froo stuff, but for most part these prices should get you just about anything you want.

Dropouts, braze-ons, bottom bracket shells, and just about any thing a custom builder needs is available in steel so there’s not much reason to compromise. This availability adds to the lower cost of building with steel as well.

Steel is very easy to machine, and the tooling to do so is available and fairly inexpensive. We can make any custom part we need when we are building a custom steel frame. Welding steel doesn’t require all of the special tooling and steps that welding titanium does. It also takes less time and less electricity than aluminum welding.

When purchasing a steel custom frame, you’re paying for only about 1/2 the labor costs of an aluminum or titanium frame. Steel as a material is also less expensive than ti or aluminum, so your costs of materials are less as well.

Durability:

As a bicycle frame material, the durability of a steel frame is very good. This is evidenced by the large number of high-end, heavily used steel bikes that you’ll see out on the road everyday.

A steel frame can be bent easier than a ti frame or an oversized aluminum frame. But all in all, it holds up extremely well, and it’s ease of repair if it is bent helps add to the durability factor a bit.

Steel can rust unlike the other materials, but in my 44 years I’ve only seen about 10 or so bikes that were rusted so badly that we couldn’t fix the frame. Those bikes were all decades old, and most had been ridden extensively on an indoor trainer. Sweat is the most corrosive agent to a bicycle it seems, so if you ride a steel frame on an indoor trainer, make sure to always wipe off the sweat when you’re finished.

Versatility:

For custom frame manufacturing, steel is probably the most versatile. You’ll see every kind of high-end frame made from steel and the material is very readily available. We use steel that’s manufactured right here in the U.S. When we need something made in a custom length, diameter, or thickness, we can spec it and they’ll make it. This is not as true for the other materials.

Repairability:

Steel is the most repairable of all the frame building materials. Just about anything on a steel bike can be replaced or redone. For example, every year we have someone who’s got an old tandem that they want to bring into the new century. We can weld in a new head tube so they can use modern headsets and forks. Then we can re-space the rear end to fit modern axel widths and more gears. Then we can move the brake studs to a position for use with modern 700c wheels. All this for about 1/5 the cost of buying a new frame. This also goes to versatility.

Riding characteristics:

Steel is the standard that other materials are compared to. It’s got a lively, comfortable ride that most customers prefer. I think that everyone reading this probably had an old Motobecane, Gitane, Peugeot, Raleigh, or some other sweet steel ride that they remember fondly. The ride of most modern steel bikes is just a great, they’re just lighter weight. Titanium and steel win the ride characteristics as far as I’m concerned.

The Wrap up:

Which material you choose for your custom bike can depend on so many factors. I’ll list a few here.

Weight – If you were to come in the shop and ask for the lightest frame available what would I recommend? I would say that despite what one reads in magazines, at this point in time if you’re willing to go to the top end of any of the price ranges, you can get equally light weight offerings in all the listed materials.

However, for those who value extreme light weight I have some rules to follow:

- Paper doesn’t refuse ink – Just because a frame weight is printed in a catalog or magazine this doesn’t make it true

- Keyboards don’t refuse fingers – If someone types a frame weight in a news group, find out if it’s my Uncle Earl

- Apples to apples – Make sure to compare equal items. If a frame requires proprietary parts (special fork, bottom bracket, head set etc…) then you’ll want to weigh all the comparables. Several manufacturers take weight off of the frame, but then add it back in the fork, headset, etc…. (again with the proprietary @#$#@%)

- Don’t trust, but verify – If you’re going to pay top dollar for light weight frame, weigh that frame (and proprietary parts) on a digital scale before you assemble it. The weight should be what your builder said it would be or your money back (bike salesmen everywhere are cursing my name right now).

Cost – That one’s easy. If dollar value is important, then I would suggest steel as your best option for a custom bicycle frame in 2009 (and still in 2012). At $1,200 for a custom frame/fork, it’s a hard value to beat.

Cool Factor – If you want your friends to be blown away by the look of your new machine, I think you can do it with any of the materials. Carbon has some interesting shapes, but steel and aluminum you’ll see with some amazing paint jobs. Titanium has that really cool ‘naked’ industrial look to it. Cool factor is really a personal choice, so I have a very hard time picking a winner, but my personal favorite is something that looks classic.

Longevity – If you really want a frame that lasts forever, I will suggest steel or titanium. Even if they do break, they can be easily fixed. If you don’t care to have a frame that last 20 years or more, then any of the materials will suffice.

Ride characteristics – Basically here, I would just suggest that you ride a bike that fits you well, and buy from a shop that will work with you over time to ensure that you’re comfortable. A good shop will spend an hour or so fitting you before even suggesting a frame size. Frame material plays a factor in comfort, but your shop’s willingness to get you comfortable is WAY more important.

Overall performance:I’m a firm believer that fitting comfortably on your bike will improve your riding performance more than a frame material will. But, if a ‘best’ material must be chosen, I would suggest a frame that won’t rattle your teeth when cornering on a bumpy road. This way you won’t have to slow down as much around those corners, and you’ll be able to stay on the bike longer between rests. I find that these things are much more important to average speed than saving an ounce or two anyway.

Well there it is. I’m having a hard time not writing 10 times as much as I’ve written here, but hopefully I’ve done an OK job recounting my views on custom frame building materials based on my experiences (or lack there of).

Just in case you thought I might be an impartial judge, let me set you straight. Steel is my favorite material for the bicycle frame. It seems to be the best balance between cost, ride quality, versatility and weight for me. We all have some bias one way or the other, and I appreciate this opportunity to express some of the factors that have formed my bias towards steel. Thanks Bicycle Paper.

I sure had a great time down memory lane looking through all of the 1970’s Bicycing magazines and seeing all of the ads for the new titanium, aluminum, carbon fiber, and even (believe it or not) bamboo bicycles. I guess the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Our patent has been issued!

Our patent has been issued!