Look Ma! No Derailleurs!!

(As originally published in The Bicycle Paper in Summer of 2011

Over the last 8 years or so, we’ve seen a lot of interest in internally geared rear hubs (IGH for short). A bike with an IGH has all of the gears housed inside the rear hub instead of using traditional cogs, derailleurs and chain rings. Remember your old 3-speed (or your parent’s old 3-speed)? It’s like that, but with a lot more gears. IGH technology is an old one (over 100 years old actually), but with the invention of derailleurs, the 3-sp IGH was abandoned by most cyclists for the unlimited gearing options of the derailleur. I don’t see the end of derailleurs anytime soon, but for those who are investigating IGH, we’re trying to help you with your homework.

Over the last 8 years or so, we’ve seen a lot of interest in internally geared rear hubs (IGH for short). A bike with an IGH has all of the gears housed inside the rear hub instead of using traditional cogs, derailleurs and chain rings. Remember your old 3-speed (or your parent’s old 3-speed)? It’s like that, but with a lot more gears. IGH technology is an old one (over 100 years old actually), but with the invention of derailleurs, the 3-sp IGH was abandoned by most cyclists for the unlimited gearing options of the derailleur. I don’t see the end of derailleurs anytime soon, but for those who are investigating IGH, we’re trying to help you with your homework.

When Todd Bertram, a master frame builder here at R+E Cycles in Seattle, returned from Germany in 2003 he brought with him something special. It was a finely crafted piece of German engineering known as the Rohloff Speedhub. He’d spent almost two years in Germany, worked in the Rohloff factory, and had seen a lot of these on bicycles throughout Europe. He had a sneaking suspicion that soon, this engineering marvel would capture the eye of American cyclists as well.

A Rohloff hub has 14 speeds instead of just 3. Now the IGH rider could have the same range of gearing that would be found on a traditional 27-speed touring bike. A bicycle equipped with a Rohloff Speedhub has no derailleurs to worry about, and is virtually trouble free as far as shifting goes.

Since 2003, news of the Rohloff Speedhub slowly made the trip around the world to the United States. What used to be a curiosity is now an accepted design. Because of its trouble-free reputation, it has become a popular item with touring cyclists, and ‘go-anywhere’ cyclists. Building Rohloff equipped bicycles has become an industry in and of itself. The special hub calls for some special frame design to make life easier for the rider though. Custom frame builders all over the U.S. are trying to design adaptations for their touring bikes to accommodate customers who are requesting this new hub.

As the builder of Rodriguez Bicycles, we got lots of questions from curious adventurers, but we didn’t start getting a lot of orders until 2009. Since then, sales have ballooned. We’ve seen our sales of Rohloff equipped bikes double each year over the last 3 years. As of November 2011, Rodriguez Bicycles has become the number one builder of Rohloff equipped bicycles in the United States as confirmed by Cyclemonkey, the exclusive U.S. Rohloff importer. (Probably the reason we were asked to write this article).

Who wants an IGH? While most of our Rodriguez Touring bikes are still equipped with derailleurs (just Shimano these days) higher end touring cyclists have been looking for alternatives to derailleur equipped bikes. This is because Campagnolo, SRAM and Shimano have all but abandoned the high-end touring market. Instead, the big 3 have focused their advertising and development on racing equipment that’s expensive, doesn’t hold up for touring, and limits the gearing ratios too much for touring. Shimano still has a some great derailleur options for the sub $2,500 bike market, but for the high end, a lot of folks are now considering the move away from derailleurs.

Another customer who has interest in IGH is the urban commuting customer. Commuters are very hard on their equipment, and some of them are very attracted to the idea of a bike specifically designed as a trouble-free commuter.

What are the IGH options? With the worldwide popularity of the Rohloff Speedhub on the rise, Shimano has taken notice of this new market as well. Shimano has been building some IGH hubs for several years, but their offerings have always been suitable for more of an urban commuter bike rather than a serious touring bike.

Last year, Shimano introduced their first serious entry into the field of IGH touring hubs, the Alfine 11. Now that Shimano is making a run at the high-end IGH market, that has spawned a lot (and I do mean A LOT) of IGH questions from around the world. People (as well as us) were hoping that the new Shimano hub would give them Rohloff performance at Shimano prices. As a major Rohloff builder, a lot of those questions have come to us.

Last year, Shimano introduced their first serious entry into the field of IGH touring hubs, the Alfine 11. Now that Shimano is making a run at the high-end IGH market, that has spawned a lot (and I do mean A LOT) of IGH questions from around the world. People (as well as us) were hoping that the new Shimano hub would give them Rohloff performance at Shimano prices. As a major Rohloff builder, a lot of those questions have come to us.

When the The Bicycle Paper asked me to write an article comparing IGH hub options, Jeremy and I were actually in the middle of answering those very questions in the form of an FAQ series on our website. So, as it happens, we have the answers:

In addition to Rohloff equipped bikes, we have now built and sold several bikes with Shimano IGH hubs on them as well. Our experience with the different hubs shows us the best use for each.

We’ll compare 3 different hubs (the 3 we’ve built with): The Shimano Alfine 8-speed, the Shimano Alfine 11-sp, and the Rohloff Speedhub 14-sp. Shimano does make some lower end 8-sp IGH hubs (Nexus), but this article is ‘geared’ toward the more serious cyclist.

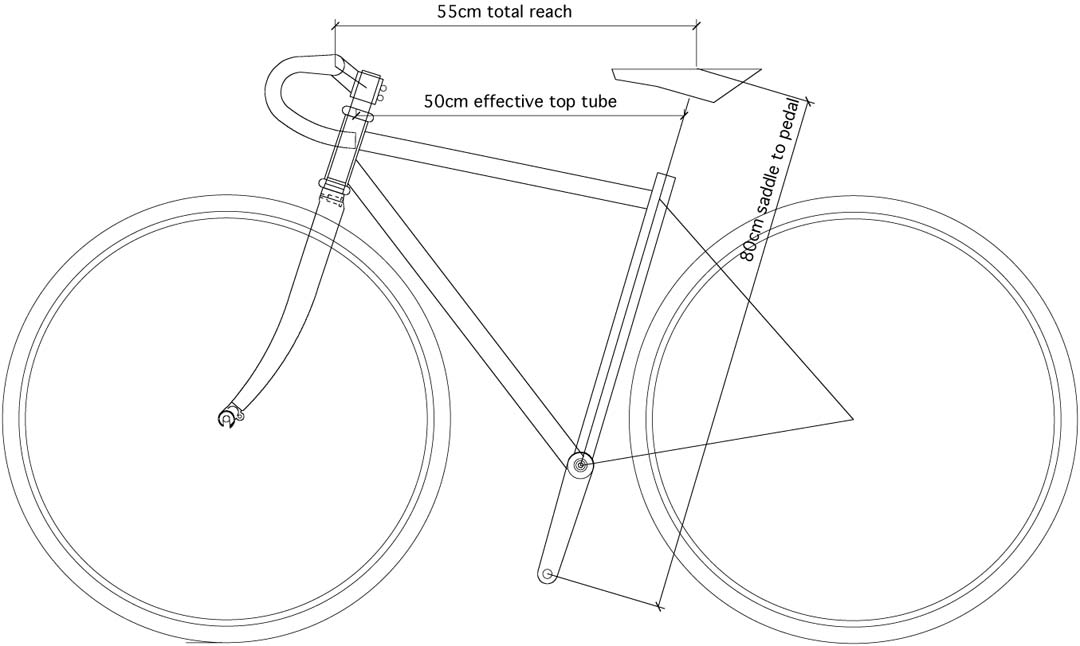

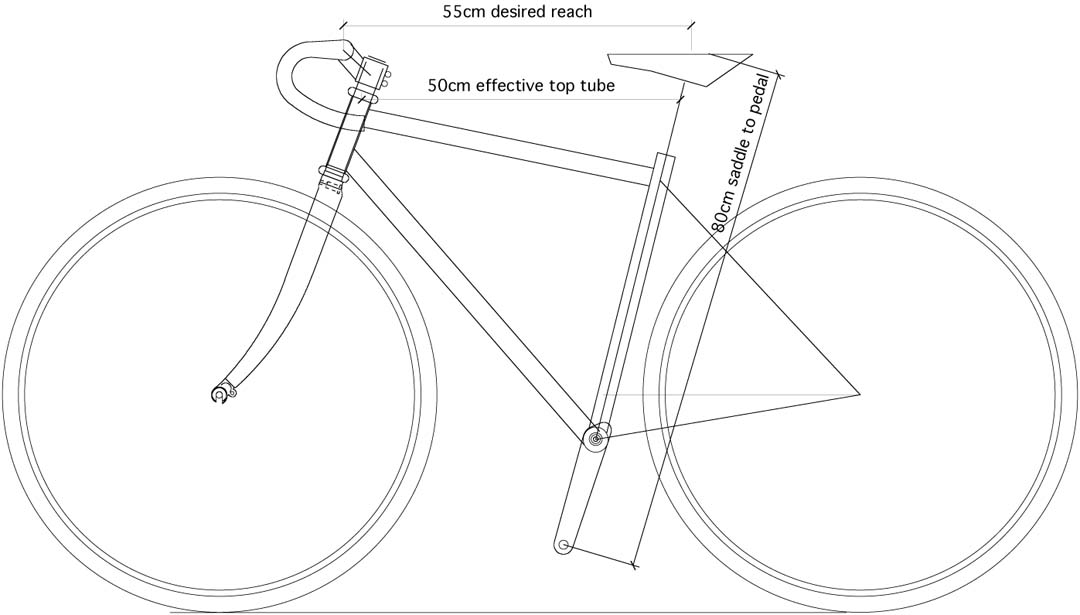

You’ll need to be familiar with a few terms:

Gear Range: This is the % of gearing change from the lowest to the highest gear. A good range % between high and low is important for touring. ie. the higher the better. Unlike a derailleur system, for the IGH the gear range is forever. A standard modern day touring bike will come with a gearing range of about 450%. It can easily be adjusted to about 600%, but the 450% gives us a good starting point. By comparison, an old 10-speed bike from the 1970’s would come with a range of 250% or so.

Gear Ladder: Another thing to consider is what we call the Gear Ladder. The Gear Ladder is the % of distance between each individual gear change. On a derailleur system this is adjustable by using different cogs or chain rings, but for an IGH, you bought it, you got it.

We’ve built several urban commuter bikes with this hub, and even a few sport/fun tandems.

- This hub is limited to 308% gear range. More than the old 10-sp, but not really enough range for serious touring.

- The Gear Ladder is very uneven. Ranging from 1st gear, it looks like this: 23%, 16%, 14%, 17%, 23%, 16%, 14%.

- Wheel attachment is bolt-on only, so no quick release rear wheel.

The gear range is 409%. It doesn’t quite get you to the range of a stock touring bike, and nowhere near the range of the Rohloff.

- Although Shimano originally planned an evenly spaced Gear Ladder, the final result was disappointing to many rabid IGH fans.

- The spread between first and second gear is a whopping 30% jump. The ladder runs even 17% and 18% for the rest of the gears, but that first 30% jump is really big.

- The absence of a quick release makes this hub less desirable for many serious touring cyclists as well.

- Also, for you belt drive fans, use of a belt drive on either Alfine hub will limit your tire width as well.

The King of the IGH! For the truly serious touring cyclist, the choice is the Rohloff Speedhub. We’ve built touring bikes, mountain bikes, and serious tandems equipped with Rohloff Speedhubs.

- The Gear Ladder is a uniform 13.6% all the way through the range.

- The Speedhub can also be ordered with a quick release axle or a bolt-on axle.

- The design allows for better belt drive/wide tire compatibility.

All in all, the Rohloff is better suited for the customer who wants an IGH, and wants a real replacement for their touring derailleur setup.

The serious touring cyclist will still have to choose between derailleurs or the Rohloff Speedhub.

Since a high quality custom touring bike will run you about $2,000 in our shop, a serious IGH touring bike turns out to be quite a bit more expensive. Even so, many folks are choosing to go that route in order to have the convenience and low maintenance of the Rohloff. We run about 70% derailleurs, and 30% Rohloff for the touring bikes at this point.

If you’re considering a Rohloff or other IGH equipped bicycle, the FAQ section of our website has a dozen or so articles comparing, contrasting, and listing all of the pros and cons of each design.