Choosing the right tandem fork

A voice of experience

For those who don’t know us, here at Rodriguez Bicycles we have been building tandems in the United States for over 40 years now. That makes us one of the oldest, if not the oldest tandem manufacturer still building tandems in the US.

All forked Up!

(Scary story of using the wrong fork in a tandem)

My first person experience with a road bike fork installed into a tandem dates back to 1995. It happened to be a carbon fork in this story, but my advice would’ve been the same if the fork were light steel or aluminum. Carbon forks were not nearly as good back then, and I would even say that they were unpredictable.

One of our bike representatives (we’ll call him Jim) was visiting the shop, and wanted to show me his new racing tandem. He worked for a very large company (we’ll call them Company X) that from time to time built tandems when the market was booming, and this was one of those times. When he showed me his tandem, he pointed out that he had installed a new carbon fork “like the ones that they ride in the Paris Roubaix”. I told him, “That is not a tandem fork.” He said, “Well, they ride them in the Paris Roubaix on cobblestone roads.” I said, “I don’t care, that fork will break in that tandem.” He replied, “The engineers at Company X said it will be strong enough.” I said, “From my experience, I think you’re NUTS if you race that tandem with that fork!” Jim decided to listen to the Company X engineers instead of me.

It was only a month or so later when Jim stopped by for his routine visit. It was kind of hard to talk with him as his jaw was wired shut. It was actually just as hard to recognize him as it looked like someone had taken a baseball bat to his entire face and head. As it turned out, the fork broke. Apparently a large part of the fork wound up entering Jim’s face underneath his chin, and exiting through his cheek (Ow! That’s gotta hurt!). I didn’t spend a long time with Jim at this visit as he was obviously uncomfortable, and I suppose embarrassed. Needless to say, he didn’t put another under-weight fork in his tandem though.

While it was really tempting to say “I told you so”, I felt so bad looking at Jim that I steered clear of that infamous saying. I did learn a valuable lesson about my instincts though, and I’ve never felt bad about telling someone that they are putting themselves in danger when they use under-weight critical parts on a bike or tandem.

Article overview:

We love our tandem customers. We love them so much that we want them to stay healthy and live a long time. The tandem industry has had a couple of boom years as of late, and so it goes that lots of newer companies have jumped in to try and take advantage while the gettin’ is good (history repeats itself). Some of these companies already build bicycles and are just now adding tandems to their line-up. Others are simply brand new companies that appeared in the last decade or so. These companies will be in the tandem world for a while, and then a lot of them will exit when sales slow back down in a few years.

Why would I write this article?

When a rider gets hurt (or worse) on a tandem, it hurts the whole tandem industry. I don’t want anybody to get hurt on their tandem whether they ride one of our bikes or not. I feel that our extensive record in the tandem world can help to steer us away from past mistakes (pun intended). A tandem is a completely different animal than a single bike (or half bike as I often refer to them). When it comes to underestimating the stresses on tandem components, there are several mistakes that some tandem riders and even some in the industry have made through the years. I’m hoping that an article like this one can help everyone to avoid making those same mistakes. Although we welcome every manufacturer to the fray, even if it’s just for a short while, we want to keep things safe and fun for those unique folks who enjoy riding tandems.

OK. With that in mind, let’s narrow our focus a bit for this article. The flagship of most tandem lines (including ours) is the uber-light tandem, right? (Even though most of them are ‘fudging’ their published weights).

A Fork in the Road

In this article, I will focus on one aspect of building a super light weight tandem….the light weight tandem fork. If you’ve been in this industry for as long as we have, you’ve learned that a fork has to be specifically designed for use on a tandem (some have learned the hard way). So, if you’re into high performance, uber-light tandems, or want to learn about the engineering challenges of building a tandem specific fork, this article is for you.

Building a super-light tandem takes a lot of heavy thinking

At Rodriguez, we’re certainly no stranger to building uber-light tandems. As a matter of fact, we’ve built probably some of the lightest verified tandems in the industry. Funny thing about tandems though, even if they are super-light, is that they are supposed to be built using components suitable for tandem riding. This is especially true for the fork. For instance, if a manufacturer specifically states that their forks are NOT recommended for a tandem, then it stands to reason that the fork shouldn’t go onto a tandem….right?

If you poke around on the websites of companies that have specialized in tandems for 20 years or more (including ours), you’ll find that they all recommend using a tandem worthy fork on a tandem.

About our Carbon Footprint:

In our shop, we use a lot of carbon forks. We have nothing against them, and we use them all the time on race and sport bikes. We probably sell as many single bikes with carbon forks as we do with steel forks. Over the years, we’ve used many carbon forks on tandems as well. We are not concerned about carbon as a material. Our concern is in educating the tandem cyclist about the need for a MUCH stronger fork than is required for use on a single bike. So Carbon Junkies, please don’t flame me.

Example:

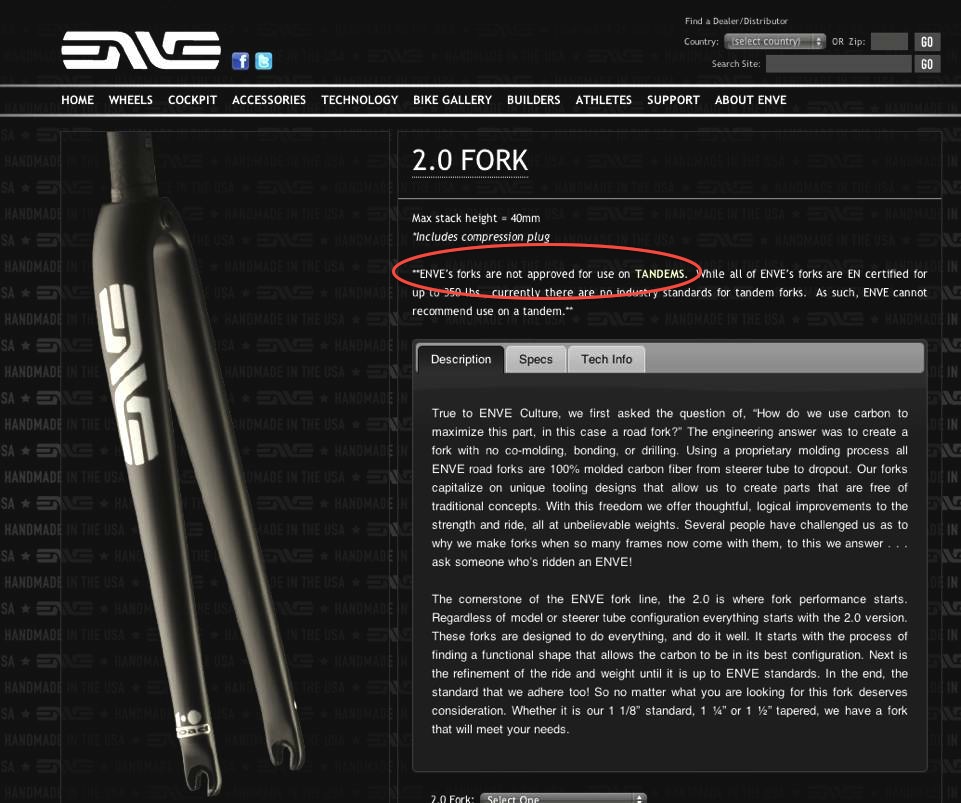

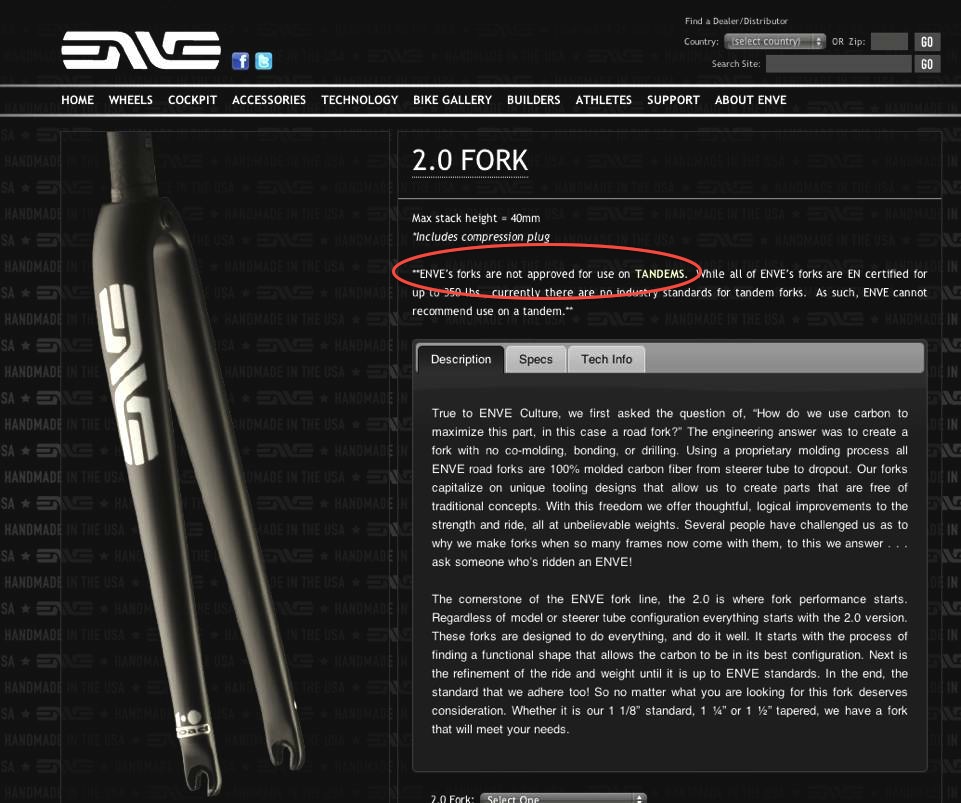

Enve, one of the industries main manufacturers of carbon forks (and our favorite race forks), specifically states right on their main web page that their forks on NOT for tandem use.

How does all of this relate to tandems?

Most carbon fork makers dropped out of the tandem market over the last few years, including our favorite. There are still a few heavier carbon forks that are recommended for tandem use, so if you want a carbon tandem fork you can get one. In the absence of the really light carbon tandem forks, some riders (and manufacturers) are throwing caution to the wind and installing ultra-light carbon race forks on their tandems to save a few ounces. I’m here to tell you, if you’re looking to save weight on your tandem, there are plenty of ways to do that without resorting to an unsafe fork that isn’t designed for the rigors of tandem use.

See for yourself

A quick web search for images of ‘racing tandems’ will turn up literally hundreds of photos of tandems using the ENVE 2.0 fork pictured here, even though the Enve company specifically stresses that this fork is NOT for tandem use.

Weight for it……

The theory goes like this: “Enve puts a weight limit of 350 pounds on the fork, so as long as we don’t go over that limit, we’re golden!” Realize that this weight limit includes the rider, all the rider’s gear, clothing, water, etc.., and their bike. That same internet search (along with little common sense) will show that a huge portion of these tandem teams are certainly at, or even greatly exceeding that weight limit. The problem with that theory is that it doesn’t say “OK for tandems up to 350 pounds” and there’s a difference. Read on to see why a weight limit for a single bike is different than a tandem recommendation.

Realize, Enve is our favorite carbon fork manufacturer and we use a lot of their products. If Enve made a fork recommended for tandem use, we would use it on our tandems. We want to see this company thrive, and that gets difficult if someone gets hurt on one of their forks.

Now, after four decades in the business, we’ve just about seen it all. History seems to be repeating itself, and the mistakes along with it. We’ve seen companies (and customers) make these mistakes before with devastating results. Recently in our repair shop, we’ve seen some dangerous close calls (on other brands of bikes) and thought it was about time to write an article to educate you, the rider, as well as any in the industry who will listen about the dangers of using non-tandem forks on tandems. Some of these close calls were even on tandem recommended carbon forks that were just past their prime.

A Warning

When it comes to choosing a fork for your tandem, DO NOT choose one that the fork manufacturer will not recommend or warranty for tandem use. I strongly recommend that if you purchase a tandem (used or new) with a 3rd party carbon fork in it, research or email the fork manufacturer to verify that your carbon fork is tandem rated. If you’re not sure, don’t use it.

A broken fork is often a catastrophic event, and on a tandem it’s a horrifying thought. Take it from us, there are better ways to save weight than to sacrifice safety.

Something else everyone should know is that carbon fiber forks that use carbon fiber steering tubes are not designed to last forever. Tandem recommended or not, any fork that uses a carbon fiber steering tube should be inspected occasionally and replaced after its life expectancy is over.

Alright, on with the article

OK, so why isn’t the maximum weight limit the same as a tandem recommendation?

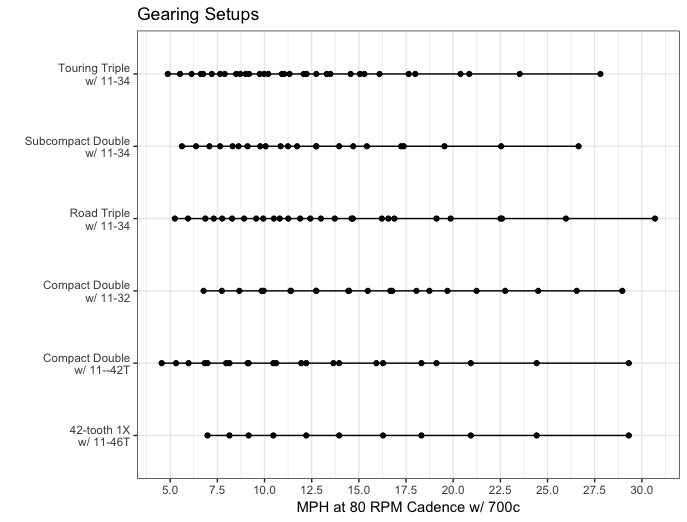

It would seem on the surface that the fork’s maximum weight rating would be the same for a tandem as for a single bike. Here’s the problem, and it’s actually a good problem. People ride faster on tandems. If you are a person who rides about 16 ~ 18 mph on your single bike, and your riding partner averages about the same, then on a tandem you will ride faster. You’ll probably ride more like 18 ~ 21 mph when you are riding together. If you’re a person who rides 45mph down long descents, then you’ll probably ride that same descent over 50mph on the tandem. That extra speed (velocity) amplifies the amount of energy impacting your fork greatly. Instead of a maximum weight limit, maybe the fork manufacturer should recommend a maximum energy limit, or at least a recommendation that takes into account weight and speed.

Some science and stuff

There are a lot of forces at work when trying to determine the amount of energy affecting your fork, and a lot of different equations to determine that. In all of them, there are more stresses on your fork when more speed and/or weight is applied. We need to select one formula to use here, and we used kinetic energy as it accounts for both weight and speed. The formula to determine

kinetic energy is

E=½MV² (Energy = ½Mass X (Velocity X Velocity) )

Now, I’m sure scientists who read this are thinking “what about acceleration, weight distribution, force, etc..”? Someone with more knowledge and time than I could write a paper on the subject, but for the sake of brevity, I had to boil it down to one easy equation. Rest assured that any equation used will show more stress on the fork if more weight and/or speed are applied.

Here’s how much it changes the mixture: 350 pounds traveling at 21 mph will impact the fork with 35% more energy than 350 pounds traveling at 18 mph. Rough surfaces, pot holes, braking, etc…. will all put 35% more impact on your fork with just that slight increase in speed. And this example is not really a very realistic one.

Now let’s visit the real world. Most people riding the uber-light fork on their single bike do not weigh anywhere near 350 pounds. Let’s use me as an example of the average uber-light fork rider as I ride a bike with one. 180 pound rider with 20 pounds of bike and gear = 200 pounds. As a tandem team, let’s say that a fit team could have a 180 pound captain, 135 pound stoker, and 35 pounds of bike and gear (helmets, wallets, sunglasses, clothing, shoes, phones, any accessories, etc…) = 350 pounds total weight. This even keeps our tandem team right at that weight limit of the Enve 2.0 fork.

Using our kinetic energy equation, the amount of force that the fork is subjected to in this tandem team is 270% more than me on my solo bike. This is assuming a modest average speed gain of just 3mph (18mph ~ 21mph). If we put the speeds at 45mph for the solo rider, and 55mph for the tandem team, the difference is even greater at 300%.

So, at the least, the fork is being subjected to 35% more force than it is designed to take. In a real life scenario, the fork is being pushed up to 300% over its design specifications. For some components, these extra forces may acceptable, but for a fork, I feel that there is no need to push those limits and to accept that risk.

The Wrap Up

Rodriguez uber-light steel tandem fork

We can build an extremely light weight tandem without compromising performance or safety. A lot of manufacturers eliminate the lateral stiffener tube to save weight, but that affects performance more than safety. Some use wheels that are built super-light for solo bikes, but that’s a durability issue. Using a fork that is too light is a safety issue and should not be done by a rider or a manufacturer.

What do we do at Rodriguez?

For the time being, we use exclusively steel tandem forks on all of our tandems, including our new uber-light 25.8 pound model. That weight is verified and guaranteed on our digital scale here in the shop. We have a full repair shop, and we service every make of tandem every year. We’ve seen every brand and every model here over time, and we’ve weighed all the light ones. Our Rodriguez uber-light steel tandem is lighter than any other tandem that’s ever been in our shop regardless of the frame/fork material. Our bike has no compromises, and even has a steel fork, aluminum cranks, a lateral stiffener tube and a tandem wheel set. There’s no reason to compromise performance, weight, or durability if you want an uber-light tandem from Rodriguez.

Visit us soon, we’d love to build your new ride!