In recent years, we’ve seen a rapid evolution in gearing options for bikes of all types. There are new options that have expanded choices for certain riders, and some options (arguably very useful options) have gotten pushed to the side. Rapid changes in “standards” are nothing new in the bike industry, and they tend to cause a lot of confusion for consumers and industry professionals alike. To clear things up, here’s an overview of your options as they stand going into 2020.

The Cassette

Over the past few decades, advances in cassette technology have mainly been aimed at squeezing in more cogs. In the 80s, even the highest-end drivetrains had just six cogs in the rear. 13-26 was considered standard. These days, high-end drivetrains use 11, 12, and even 13 cogs. This has created narrower cogs and chains as well as pushed road bikes to move to a wider rear triangle to accommodate more cogs and disc brakes. These thinner chains and cogs tend to wear out more quickly, however, so that’s been a bit of a trade-off. We’re starting to see some mountain bike drivetrains return to nine (and even seven) speed drivetrains to make them more robust.

As for the actual shifting performance, the woes of the 10 speed era have mainly been ironed out. Shifting is mostly excellent across the board. The new radical shift in cassette technology is range. Driven by mountain bike design, cassettes have ballooned in size. Just a few years ago, a cassette with a range from 11 teeth to 32 teeth was considered a large cassette. These days we’re seeing cassettes as wide as 9 teeth to 50 teeth. That’s a gear range of over 500%. The catch is that those are for single chainring drivetrains, also called 1X. All the shifting is in the cassette, so it needs to have a wide range. The only way to get that kind of range before was to use a triple chainring crankset. Why choose one over the other? Which is better for the rider? Well, that depends.

The rear derailleur has traditionally been used to fine tune your gear selection. Adding more cogs, like having eleven instead of nine, allows for smaller jumps between gears and therefore more control over the gear ratio. Large jumps are made by the double or triple chainring, then the rear was used to find a gear that was “just right”. The new selection of wide range cassettes have much bigger jumps between cog sizes. For some riders this can be frustrating when they can’t shift into a gear that feels perfect for the terrain they happen to be on at the moment. For other riders, this isn’t much of a big deal. They value the simplicity of using a single shifter and will either push harder or go slower when they can’t get the gearing perfect. There seem to be plenty of both types of riders so having multiple options is a good thing.

Chainrings

Chainring configuration has also seen a lot of change recently. We see three major shifts: an expansion in gearing options for double cranks, the emergence of “one-by” drivetrains, and the so-called death of the triple.

Double Chainring Drivetrains

Not so long ago, there were essentially three choices in front gearing for double cranks. The traditional choice, suitable for racers and the manliest of manly men, was the 53/39-tooth combo. “Compact” gearing, 50/34-tooth, was initially rolled out as an alternative to triple cranksets and effectively became the industry standard with its more forgiving gear range. Finally, cyclocross ended up with its own chainring standard of 48/36-tooth.

Compact gearing worked well for a lot of riders, but never really lived up to its intended purpose of replacing triple cranks. Triples offered the option of getting ridiculously low gear ratios, but the compact double’s 34-tooth small ring (smaller rings mean lower gears on the front) wasn’t actually all that low a gear.

Enter the All-Road Bike. A growing number of cyclists today want a bike that can go back and forth between paved roads, forest service roads, gravel roads, and single track. That’s a lot to ask and also part of what’s fueling all of this drivetrain evolution and mutation. While the 46/30 has become semi-standard on bikes like this, combinations as low as 42/24 are available. Higher gears are sacrificed for all-terrain capability. Many see it as worth the trade off, but drivetrains may not be done evolving just yet. The recently released GRX series from Shimano will shift an 11-42 in the back while keeping a compact double 50/34 in the front. That’s a lot of range and it’s developments like this that lead people to pronounce “the triple is dead”

The 1X (one-by), or Single Chainring Drivetrain

Like a lot of recent developments, the 1X drivetrain comes from the world of mountain biking. Riders who were pushing their mountain bikes to the limit over rough and varied terrain wanted to simplify things and take one variable for failure out of the equation altogether. The front derailleur was seen as the best part to go because when it did malfunction, it could stop a rider in their tracks. Thus, the 1X was born. It’s a little more complicated than just removing the derailleur. Chainrings were redesigned to retain the chain instead of letting it go for shifting. Rear derailleurs had clutch mechanisms added to keep the chain steady over bumpy terrain. This is also where the ultra-wide range cassettes began to develop. Mountain bikes need gearing that’s able to shift to a very low gear and do it quickly. Off-road terrain can become suddenly very steep and having just one control that moves the gear quickly and surely has been great for mountain bikers. They can make huge changes in gear ratio without the fear of dropping the chain off the chainring.

This drivetrain configuration has made the jump to all-road and gravel bikes now, for some of the same reasons. There’s something to be said for simplicity and dependability when your bike is covered in mud and you’re trying to make it up an 18% grade made of soft dirt. The trade off is the range, but cassettes that go from 10 to 50 teeth mitigate that aspect quite a bit. A 500% range is nothing to sneeze at. The disadvantages have to do with the cassette, as I discussed above. Big jumps between gears are not for everyone. Still, for some, the 1X fits their needs exactly. From a builder’s perspective, we just see it as one more tool in the toolbox for making someone a bike they love. It seems to be sticking around and we’ve met more than a few that don’t want to ride anything else.

Triple Chainring Drivetrains

Well, what about the triple? It’s death has been pronounced before, back in the 80’s. Back then, the triple (a crankset with three chainrings) fell out of favor on road bikes and was relegated to touring bikes and mountain bikes. “Compact” cranks with 50/34 tooth rings, the thinking went, provided plenty low gearing. It was only a few years before manufacturers again figured out that people still wanted to climb big hills on their road bikes without having to stand and mash a big gear, and the 34-tooth ring just wasn’t cutting it. Triples returned to full range of road groups. This is because no other configuration can match the gearing range of a triple drivetrain. That’s still currently true. A triple with a 53/39/28 chainring combination paired with an 11-36 cassette has a high gear of 122.3 inches and a low gear of 21.5 inches. That’s a range of 568%. That means the triple is still king in that category.

So why are so many people willing to declare the triple dead? A triple chainring drivetrain requires a bit more setup and adjustment, but just barely. A lot of people soured on triple shifting during the ten speed era I referenced above. During this time, manufacturers decided to make triple shifting “indexed” the way shifting in the rear was. One set movement of the shifter moved one gear with a click. Well, that didn’t go well at the time. The fledgling technology resulted in a lot of mis-shifts and dropped chains. It really wasn’t fun for anyone. By the time the problems got ironed out, the compact double appeared and people steered away from the triple altogether. And yet, the triple still refuses to go away. Certain riders still insist on one because they love the combination of range, flexibility, and adjustability. Up until recently, it was still the only way to get truly low gears on a road bike. That aspect may have changed, but we’re not ready to count the triple out just yet. A lot of our customers ask for it and we’re going to continue to provide it as best we can for those customers. In the end, we believe it’s worth keeping the option available. The mountainous climbs and long descents of the Pacific Northwest might have something to do with that choice.

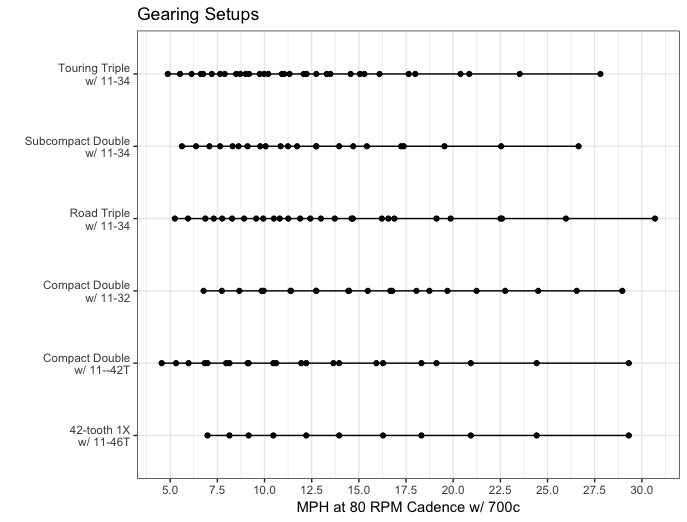

We’ve put together a chart to help visualize what the differences between these options are in a linear perspective. Here, you can see not just the range, but what the jumps between gears look like as well. (Thanks to Logan for the chart and his input on this post)

I hope this answers any questions you might have had regarding what’s going on with bicycle drivetrains these days. Currently, we have more options than ever before and that’s not a bad thing. It helps us hone in on what will be best for each individual customer, and as a custom shop that’s exactly what we want. We’re not going to say goodbye to the triple anytime soon, but that doesn’t mean we won’t say a warm hello to the new developments out there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.