A quick summary of the compromises that have to be made when designing bicycles for people under five feet, five inches tall.

Compromise 1, Accept Toe Strike

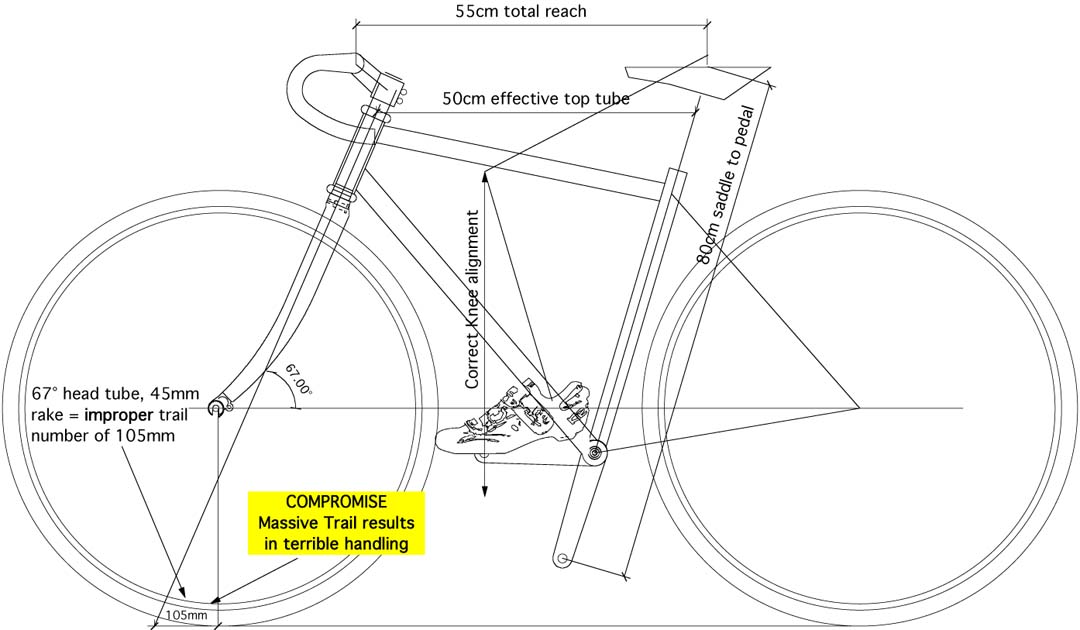

Some manufacturers choose to compromise safety instead of handling. By designing a bike for proper trail numbers, and a short top tube, this manufacturer has designed a bicycle that is very dangerous when trying to avoid an obstacle (like a car door or pedestrian) when riding. At Rodriguez Bicycles, we no longer build with this much toe strike because we have had to buy back so many small bikes over the years for this reason. No matter what someone tells you, you’re not going to get used to it, and too much toe strike is not OK.

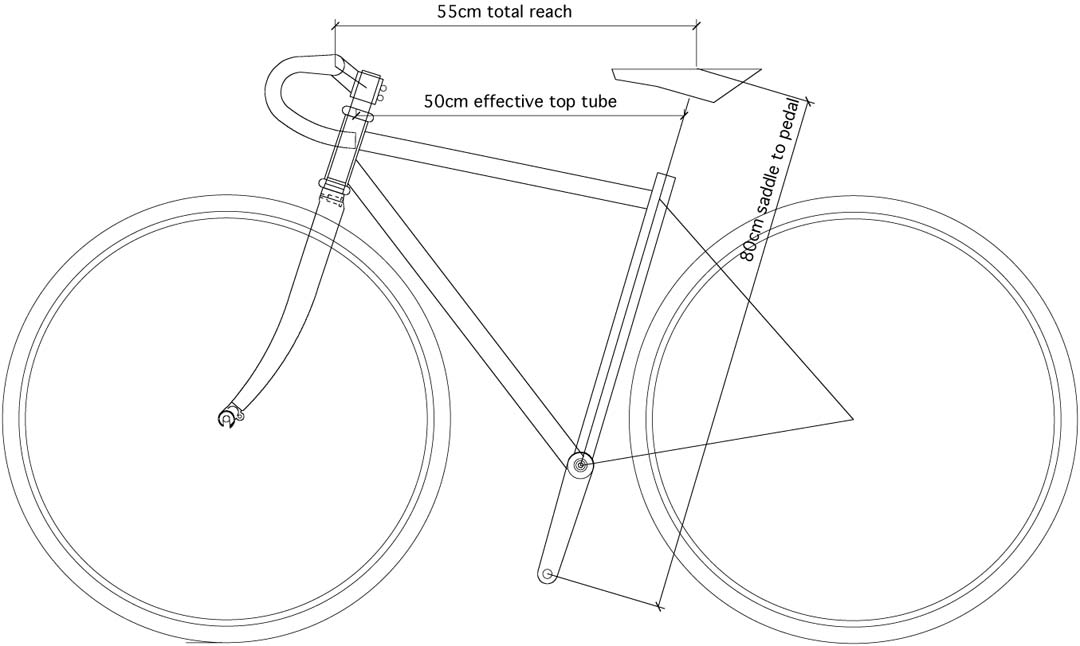

This drawing is an exact re-creation of an actual bike that came in for repairs because the customer crashed while trying to avoid a car door. The rider was confused as to why they went down, but was sure they didn’t hit the car door.

The picture on top shows that the bike looks perfectly fine, and normal to the untrained eye. The fit measurements line up just right for most women around 5’3″ tall. The same drawing on the bottom shows the issue of toe-strike.

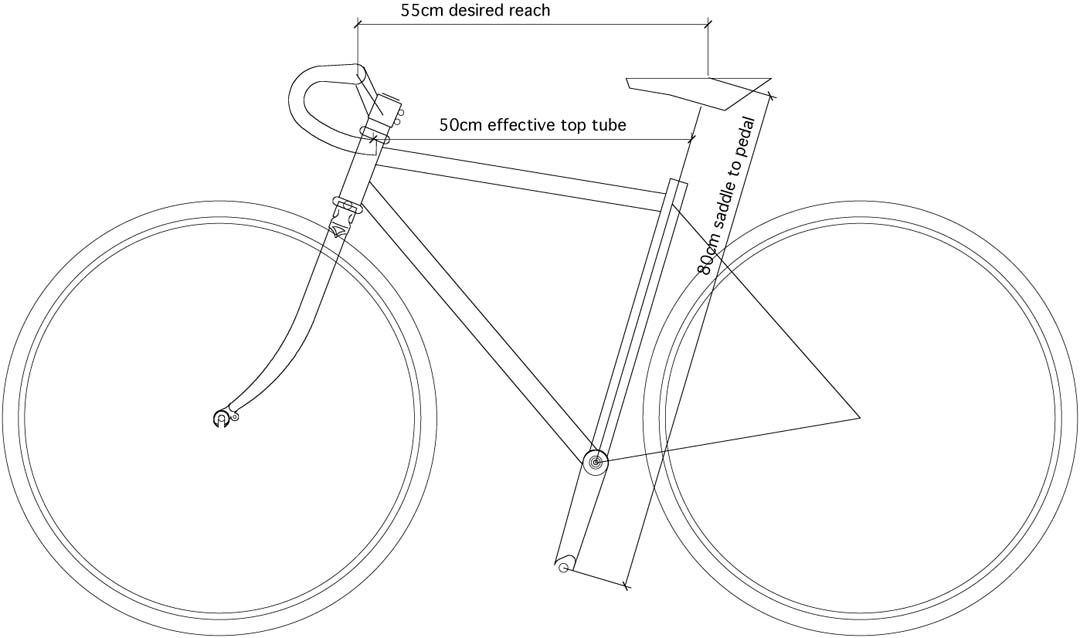

Compromise 2, The Magic Top Tube

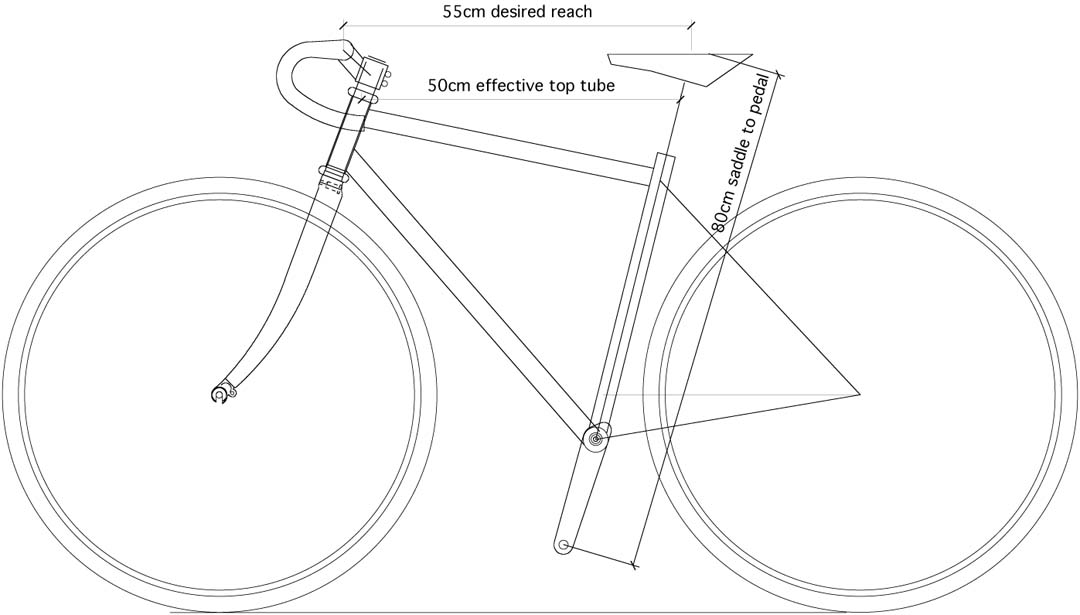

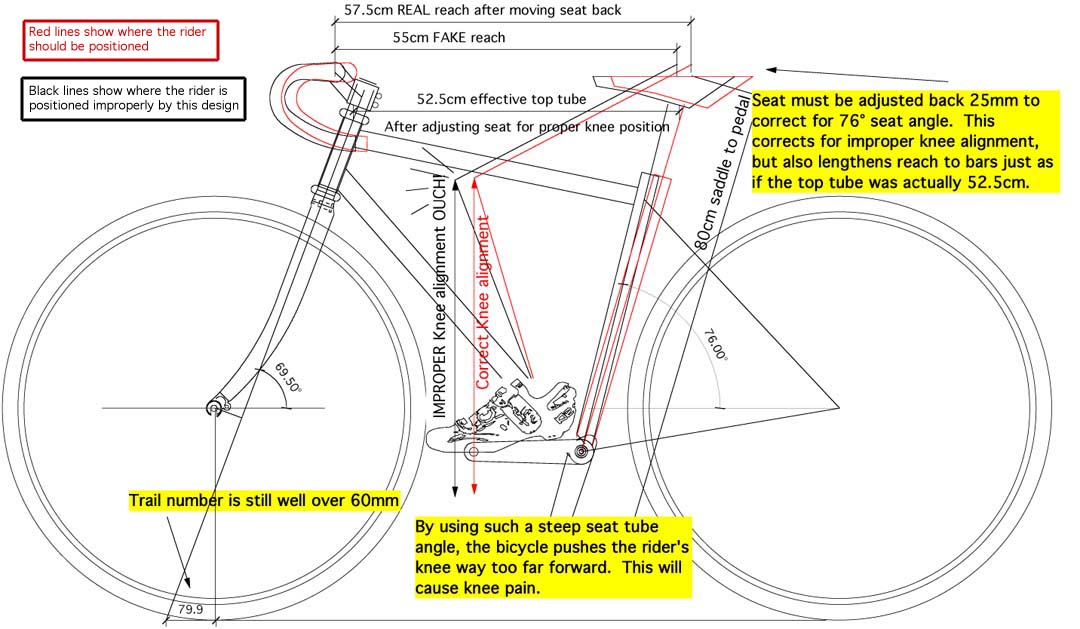

On the face of things, this second bike has no toe overlap, acceptable handling geometry, and the right fit numbers. What the untrained eye doesn’t see here is that this is actually a trick. The seat tube angle has been designed very steep, so the top tube is artificially shortened. This way the manufacturer can list the bike in a catalog with a short top tube.

In real life, this is the worst compromise for most riders because it makes the reach almost impossible to shorten. Riders that have bikes like this soon find out that their knee is way too far forward and they have developed knee pain when they ride long distances. The only way to correct it is to push the seat way back, effectively lengthening the reach to the bars too far for a shorter rider. Now the rider needs a stem that’s shorter than any thing available. Unless your fit numbers call for a really steep seat angle, I recommend against this option.

On the top, you can see that this bike looks normal. On the bottom, you see that this is actually the worst way to design a small bike with 700c wheels if you consider fit and control as important. Many, many companies use this slight of hand to pass off a small bike as ‘women’s specific’ design.

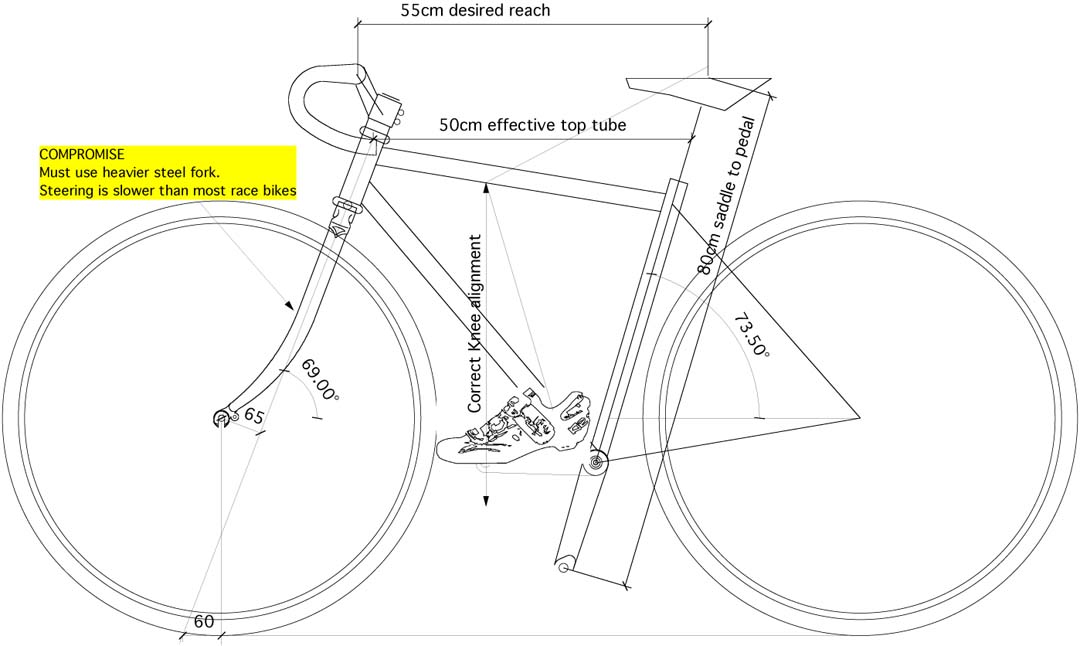

Compromise 3, Ignore Control All Together

One way to get the big wheel out of the way of the rider’s foot is to slacken the head tube angle…..a lot…like a chopper. This option says “let’s build the bike to fit right, and we don’t care how it handles”. The bike drawn below is an exact re-creation of an expensive titanium custom bike that a 5′ 2″ tall woman brought in because it didn’t handle well. When I rode the bike, I would liken the handling to my grandfather’s 1966 Ford pickup without power steering. ie….it was a chore to steer this bike.

Although this option allows for a carbon fork, I suggest strongly that you try it for a weekend before you invest in a bike built like this. I also suggest that you try compromise 4 and 5 as well. I think that you’ll find that handling characteristics are much more important that you may think.

On the top, you can see that this bike looks normal to the untrained eye. On the bottom, you can see the result of a ‘chopper-style’ front end.

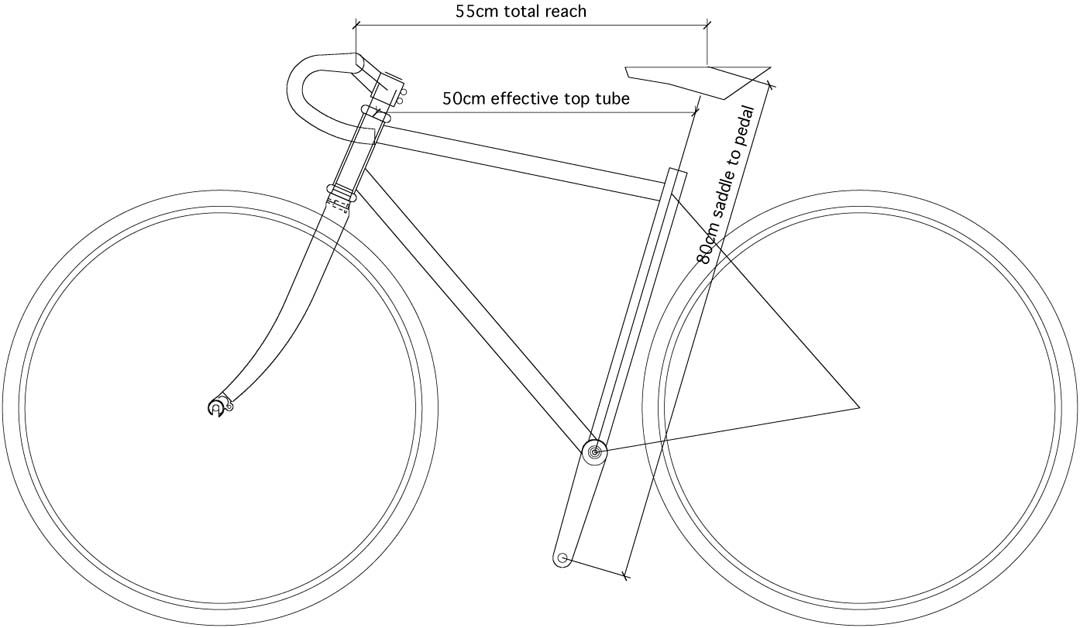

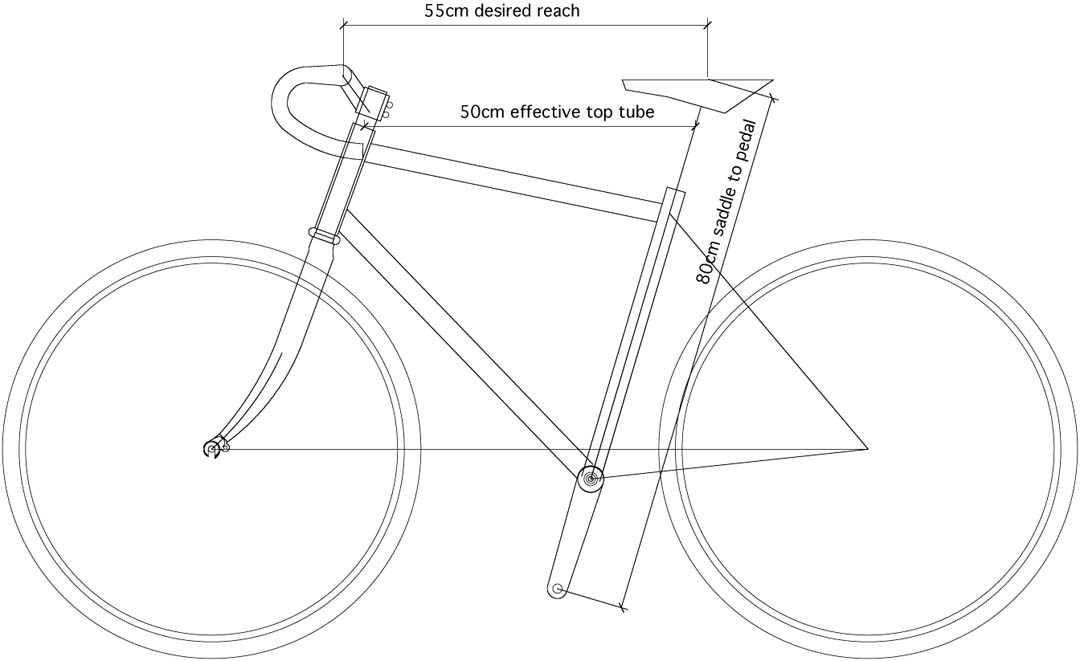

Compromise 4, Go Old-Style

The very best way to put a 700c wheel on a smaller bike is the same way that we used to do it in the 1970’s and 1980’s…..use a steel fork. By using a steel fork, we have the option to put a custom amount of rake in the fork to offset a slack steering angle. This keeps the handling characteristics correct, and allows us to build to the proper fit and knee angle.

Proportional wheels are always going to give the bike better handling, but this compromise will allow those who really want 700c on a small bike to have them. The drawbacks to this option are that the fork ends up being heavier, and you still have some issues related to large wheels on a smaller bike. Read what what a serious athlete of smaller stature has to say on that subject.

On the top, you can see that this bike looks normal to the untrained eye. Actually, it looks (and rides) a lot like the an old Peugot or Raleigh from the 1970’s. On the bottom, you can see that it results in pretty satisfactory numbers as well. This option is preferable to 3 previous options, but doesn’t really provide the petite rider with the same level of quick handling and control that the taller riders get on their bikes.

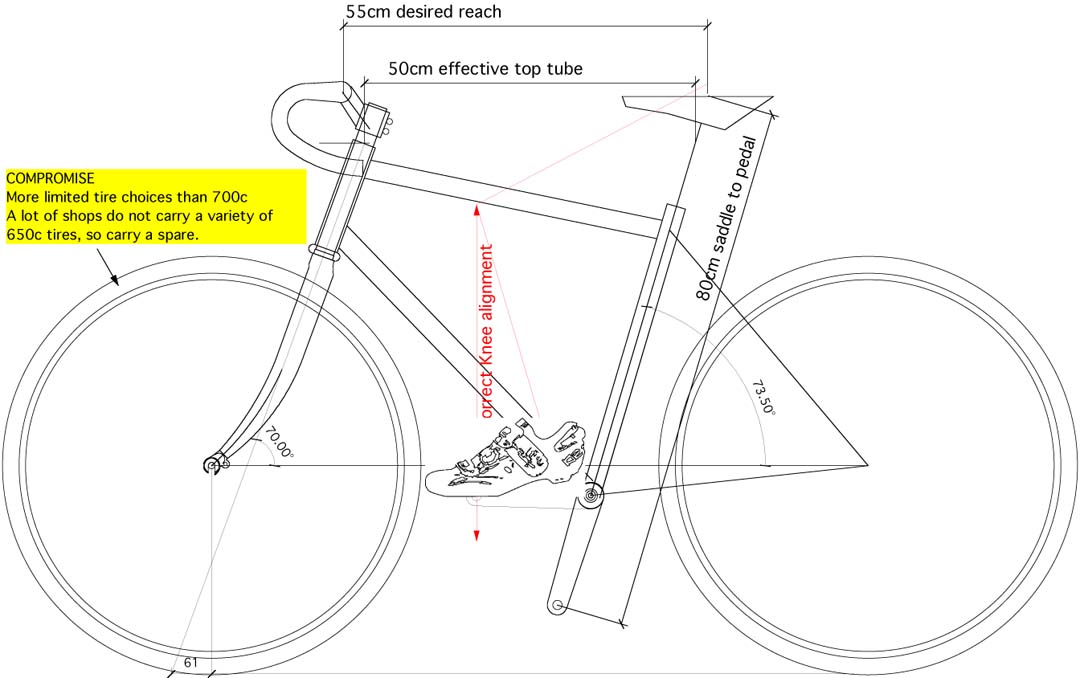

Compromise 5, Perfectly Proportional but more limited selection of tires

The very best way to build a smaller bike considering handling, comfort, fit, and speed is to use wheels that are proportional to the frame size. Using a 650c wheel allows the builder to correct for all of the drawbacks listed above and use lighter wheels and carbon fork as desired.

The drawbacks to 650c wheels are that your tire choices are more limited. The cycling industry ignores the needs of female cyclists to a very large extent, and stocking 650c tires just isn’t cool. If you ride widths from 23mm to 28mm, and you don’t mind carrying a spare, then you’ll have no problems with 650c.

On the top, you can see that this bike looks well designed and proportional. On the bottom, you can see that all of the fit measurements are right, as well as the handling geometry. The only compromise being a more limited tire selection. The petite rider can experience the exact same performance and control as taller riders do on their bikes.

There you have it. A full graphic illustration of the ups and downs of wheel sizes and smaller bikes. A lot of smaller riders and women get a lot of advice from friends who ride, but aren’t actually bike designers. We’re happy to build your smaller bike with 700c or 650c wheels. I think that it’s important that you consider the differences as explained by someone who designs bicycles for a living.

Related Items

- Find wider 650c tires at 650biketires.com

- See photo galleries of 650c bikes at www.rodbikes.com

Very good run down. Concise, informative and easy to follow.

Awesome summary, thanks ! I had difficulties to grasp the big picture with the individual posts, now it’s cristal clear. And thanks for such a nuanced view backed with so good schematics.

If you’re looking for other geometry topics to address, I’ve always had difficulties to understand the sloping geometry. I repeatedly hear the argument that it allows for stiffer frames since the resulting triangle is smaller. But for me, the rigidity is lost in the longer seatpost, isnt’it ? Remains the argument of the standover clearance but a few inches are enough, aren’t they ?

That’s a good topic to address. I will put it on the list. There’s a lot of speculation that goes around the industry about why something is done the way it is, and sloping top tubes is one that I was thinking about just last night.

Pingback: Why not 26 Inch Wheels instead of 650c? | Rodriguez Bike News

hi Rodriguez!

i’m back with some sketchs. curious to know what do you think. 🙂

starting from your first example, where there is a propper fit for the rider, but a big toe-overlap:

-effective top tube 500mm

-seat angle 73,5

-head angle 72

-rake 45mm

-saddle to pedal 800mm

-reach 550mm

-handlebar level with the saddle

-with this example the stem is about 50-55mm

my question is:

what about this solution, where the entire front (wheel, head angle, rake) is moved away from the rider, but the handle bar stays in place, thus making the horizontal top tube longer, the stem shorter?

the stem will be realy short so this way the handle bar and the stem will be one part, a custom one.

HOW THE HANDLING IS GOING TO BE? what do you think? 🙂

this will be the what changes:

-effective top tube 530mm

-with this example the stem is about 20-25mm

here a photo sketch with first example, 500mm horizontal top tube,

http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8475/8150157746_0c8cb32f09_b.jpg

here second one, 530mm horizontal top tube,

http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8474/8150131293_9b5f6da8d5_b.jpg

Hi Mircea,

Sorry about the delay, it’s been a busy time at the shop! The first thing that gets neglected when we’re crazy busy is the blog.

I like your sketches, and the time you’ve spent thinking about using 700C wheels on smaller frames.

Your idea of shortening the stem to accommodate the toe overlap is good, however the length of stem you are talking about isn’t available. The handling would be the same as a proportioned larger frame, however. With a standard diameter bar (25.4mm) and an 1″ 1/8th steertube (28.6mm), you would have -7mm space between the steer tube clamp and the bar clamp if you want a stem with a length of 20mm.

Cheers, and sorry again about the delay.

hi Jeremy!

the 20mm stem problem can be solved like that 🙂

with a 60mm stem + a special handlebar that has everything 40mm moved back compared with the place where it is clamped on the stem. like in the photos from the link. what do you think? 🙂

http://www.flickr.com/photos/14752418@N06/sets/72157632070841509/detail/

Hi Mircea,

I think your bar moved 40mm back would probably be your best bet, should handle fine. You better use a stem with a removable face plate, otherwise you’ll be fighting to get the bars in your stem!

Cheers!

i want to let you know that overall i believe in the bike (frame, parts, etc) being well proportioned to the body sizes; so small body goes to small bike 🙂

in the examples that a made above i am really wondering what’s best for a small rider IF it’s needed to have the same “big” front wheel, and to not have problems with toe overlap?

1) short top tube + slack head angle + long stem

http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8206/8247127560_4f6263f44f_b.jpg

2) long top tube + steep head angle + short stem

http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8474/8150131293_9b5f6da8d5_b.jpg

Both are fine.